Last Updated on July 31, 2019

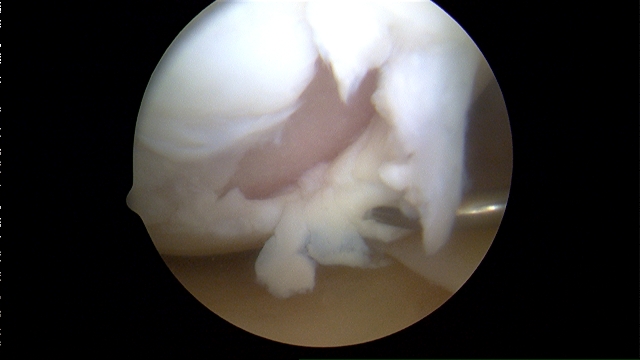

Articular cartilage injury is common and the lesions appear as tears or potholes in the surface of the cartilage. If the lesion is all the way through the cartilage, it is called full-thickness lesion, otherwise, it is a partial thickness lesion.

Articular cartilage covers the ends of bones. When the surface of the cartilage is injured, it is usually not painful as cartilage does not have a nerve supply. Persistent defects can cause degeneration of the joint. In large lesion, the bone below the cartilage loses protection, and strain on this unprotected portion of the bone can also become a source of pain. Sometimes part of the torn cartilage will break off inside the joint. Since it is no longer attached to the bone, it can begin to move around within the joint, causing even more damage to the surface of the cartilage. [loose body]

Cartilage lacks a supply of blood and nerve supply and lymphatics. Cartilage is not able to heal itself if it gets injured. If the cartilage is torn all bone-deep, the blood supply from inside the bone is sometimes enough to start some healing inside the lesion. In cases like this, the body will form a scar in the area using a special type of cartilage called fibrocartilage.

Most of these articular cartilage injuries are seen in the knee joint.

Types of Articular Cartilage Injury

The International Cartilage Repair Society has set up an arthroscopic grading system by which cartilage defects can be ranked:

- Grade 0: normal cartilage

- Grade I: In this early stage, cartilage starts to become soft with swelling

- Grade II: This stage will present a partial-thickness defect with fibrillation (shredded appearance) or fissures on the surface that do not reach the bone or exceed 1.5 cm in diameter

- Grade III: This stage presents an increased amount of fibrillation and fissuring to the level of subchondral bone in an area with a diameter of more than 1.5 cm. Patients will often complain about noise as the knee bends and soreness or trouble standing from a squatted position.

- Grade IV: An exposed subchondral bone—meaning, the cartilage may wear away completely. When the involved areas are large, pain usually becomes more severe, causing a limitation in activity.

Etiology of Articular cartilage Injury

There are two distinct articular cartilage injuries

- Focal lesions- Well delineated defects, usually caused by trauma, osteochondritis dissecans or osteonecrosis.

- Degenerative lesions- Poorly demarcated and caused as a result of ligament instability, meniscal injuries, malalignment or osteoarthritis.

Trauma in sports injuries or accidents is the most common cause of articular cartilage injury Patellar is responsible for 40–50% of osteochondral lesions around the femoral condyles. Osteochondritis dissecans, osteonecrosis, osteoarthritis are other causes of articular cartilage injuries.

Presentation of Articular Cartilage Injury

Patients present with insidious onset of pain with or without effusion, depending on the lesion etiology. Join line pain with occasional mechanical symptoms such as locking or catching may also be the presenting complaint. The most common clinical presentation of a full-thickness lesion is a loose body. It may be associated with an acute injury and a concomitant large knee effusion.

A routine complete physical examination should be performed to rule out malalignment, meniscal tears, ligamentous instability or extensor mechanism problems.

Imaging

Routine plain radiographs, including AP, lateral, and standing PA flexion views, may reveal different findings, according to cause. Joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis or cysts will suggest an osteoarthritic origin.

Osteochondritis dissecans defect can also be seen on plain radiographs, with or without a loose body. Conventional radiography may reveal no changes even with full-thickness cartilage lesions.

MR imaging remains the benchmark of articular cartilage lesions with associated soft tissue or bone changes. It allows seeing the bone structure, chondral lesions, meniscal or ligamentous pathology and bone marrow edema (bone bruise).

Arthroscopy is the gold standard and most accurate technique for diagnosing articular cartilage lesions.

Treatment of Articular Cartilage Injury

The treatment of chondral lesions depends on patient selection, daily and sports activities, age, etiology, grade and quality of the lesion. Treatment options range from conservative, through arthroscopic or open surgical procedures.

The goal of conservative treatment is to reduce symptoms, not to heal the lesion. It is considered in mild symptomatic cases or in cases with small lesions where surgery could do more harm than good.

NSAID, hormones (estrogen, growth hormone, etc), weight loss, rest, ice, canes, bracing, physical therapy are commonly used modalities.

Surgery would either repair or restore the cartilage. A reparative surgery can help fill in the lesion, but it doesn’t completely restore the actual makeup and function of the original cartilage. Restorative surgery carries out the procedure that would result in the lesion filled to the full depth by tissue identical to the original.

Specific injury, age, activity level, and the overall condition of the knee would determine the kind of procedure to be taken.

Surgical treatment for cartilage lesions is contraindicated in some cases as inflammatory arthropathy, unstable or malaligned joint, “kissing lesions” (bipolar), infection and obesity.

Reparative Surgeries

These procedures are used to stimulate the body to begin healing the injury. They are considered reparative surgeries because the lesion mainly fills in with fibrocartilage.

Arthroscopic lavage and debridement

Arthroscopic lavage washes out inflammatory mediators, loose cartilage and collagen debris that may lodge in the synovium and cause synovitis and effusion. Debridement of cartilage (chondroplasty) removes loose flaps or edges that mechanically impinge on the joint.

It is only intended to be a short-term solution, but it is often successful in relieving symptoms for a few years.

Abrasion Arthroplasty

Abrasion arthroplasty is indicated when there is an exposed sclerotic degenerative arthritic lesion. The aim is to debride the boundaries of the articular cartilage defect and breach the subchondral bone, allowing blood to perfuse into the defect forming a fibrin clot and the scar tissue (fibrocartilage) is formed cartilage. This usually is a temporary solution.

Surgeons use a blunt awl (a tool for making small holes) to poke a few tiny holes in the bone under the cartilage so that they fill with blood clots and repair the cartilage.

Subchondral Drilling

The concept is similar to microfracture, but high-speed drills are used instead of awls.

Restorative Surgery

In these procedures, the tissue is placed inside the lesion in hopes of restoring the normal structure and function of the original cartilage.

Osteochondral autografting (OATS)—mosaicoplasty

The graft is taken from a non-weight bearing area of the same knee as a donor. The optimal patient is young with a medium-sized lesion (2.5–4 sq cm). Arthroscopic debridement is followed by removal of unstable cartilage, aiming for a stable contained crater, preferably circular. The next step is the measurement of surface area and cylindrical removal of subchondral bone, as close as possible to the lesion border.

Cylindrical osteochondral plugs are harvested from a donor area to and inserted 1 mm apart, by a graduated tamp, allowing accurate depth.. The osteochondral autograft procedure has mostly been used to treat osteochondritis dissecans.

Osteochondral Allografting

An osteochondral allograft is a lot like the osteochondral autograft described above. But instead of taking tissue from the patient’s donor site, surgeons rely on tissue from another person. The osteochondral allograft procedure is mostly used for osteochondritis dissecans after other surgeries have failed.

Autologous chondrocyte implantation

This is a new way to help restore the structural makeup of the articular cartilage in active, younger patients (20 to 50 years old) when the bone under the lesion hasn’t been badly damaged, and when the size of the lesion is small. In the first surgery, chondrocytes from inside the knee cartilage are taken. These cells are grown in a laboratory.

The second surgery is done at a later date, surgery, during which the surgeon implants the newly grown cartilage into the lesion and covers it with a small flap of tissue. The cover holds the cells in place while they attach themselves to the surrounding cartilage and begin to heal.

It is accepted that the results of ACI were less favorable in patellofemoral joint lesions.

Matrix-induced ACI

The technique has two stages. First is a diagnostic arthroscopy for diagnosis and sizing of the lesion and harvesting chondrocytes which are cultivated in the laboratory and seeded on collagen membrane. The second stage is surgical, involving debridement of the cartilage defect to the subchondral plate, without bleeding, shaping to a stable crater and sizing of the defect and shaping and sizing of the membrane accordingly.

Glue is injected to the level of the cartilage surface, pressing the membrane with soft-side up to the level of the cartilage, removing air bubbles and cleaning of leaked glue. It is a suture free, less invasive and allows early mobilization.

Periosteal and Perichondral Grafting

Experiments have been done to implant tissues from the covering of bone and cartilage into the lesion. The results are promising but procedures are still in the experimental stage.

Artificial chondroplasty

Several kinds of implants are used today, most are experimental, and are for focal chondroplasty, especially as a salvage procedure in elderly osteoarthritic patients.

Rehabilitation

Patients are put on a continuous passive motion machine. Patients will be instructed to avoid putting too much weight on their foot when standing or walking for up to six weeks. People treated with an allograft are often restricted in their weight bearing for up to four months.

Exercises to help improve knee motion and to get the muscles toned and active again. At first, the emphasis is placed on exercising the knee in positions and movements that don’t strain the healing part of the cartilage. As the program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the knee’s strength and function.