Last Updated on February 27, 2021

Coccydynia, also called coccygodynia refers to pain in the coccyx region. The term was given by Simpson in 1859. However, the condition has been reported in the literature before that period too.

The coccyx is the lowermost part of the spine and is also called the tailbone. One can feel the lower end of the coccyx in the proximal part of the gluteal cleft [The groove between the buttocks]. It is right there where a tail would begin in animals.

Other names for the condition are tailbone pain or coccyx pain, coccygeal pain, coccyx pain, coccydynia or tailbone pain.

Coccydynia is much more common in women than in men.

Coccydynia is rare, accounts for less than 1% of back pain conditions.

Anatomy of Coccyx

The word coccyx is derived from the Greek word for the beak of a cuckoo bird.

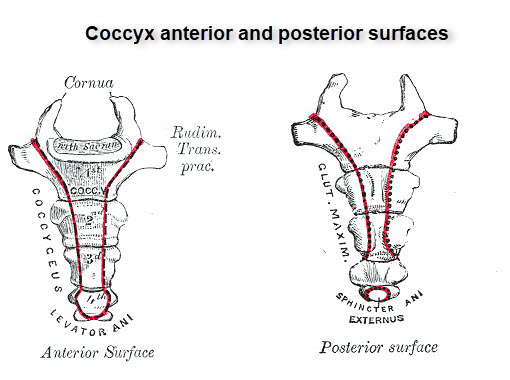

The coccyx is the terminal portion of the spine and consists of 3-5 fused vertebrae with variable disc spaces. The largest and cranial most articulates with the sacrum through a rudimentary articular process called the cornua. The attachment could be a symphysis or as a true synovial joint.

The coccyx represents a vestigial tail (so the term tailbone). The ventral side of the coccyx is slightly concave whereas the dorsal aspect is slightly convex.

The anterior surface is characterized by three or four fusion grooves serves as attachment for levator ani muscle and sacro-coccygeal ligaments.

The coccygeal ligament is the name given to the lower part of the filum terminale and it inserts onto the first segment. This is a specialized structure formed by three layers of meninges that attaches the meninges, and consequently the spinal cord, to the coccyx.

Anteriorly, the coccyx is bordered by the levator ani muscle and the sacrococcygeal ligament.

The posterior surface of the proximal-most segment is marked by coccygeal cornua [that articulates with the sacral cornua]. These form the posterior sacral foramina through which the posterior division of the fifth sacral nerve exits.

Lateral processes of the caudal most sacral and cranial most coccygeal vertebra form the anterior sacral foramen.

Anterior to posterior, the lateral edges serve as insertion sites for the coccygeal muscles, the sacrospinous ligament, the sacrotuberous ligament, and fibers of the gluteus maximus muscle.

The lateral surface of the coccyx provides attachment to sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments and fibers of the gluteus maximus muscle.

The iliococcygeus muscle tendon inserts onto the tip of the coccyx.

The attached ligaments and muscles alsosupport the pelvic floor and also contribute to voluntary bowel control.

There is limited movement between the coccyx and the sacrum.

Types of Coccyx

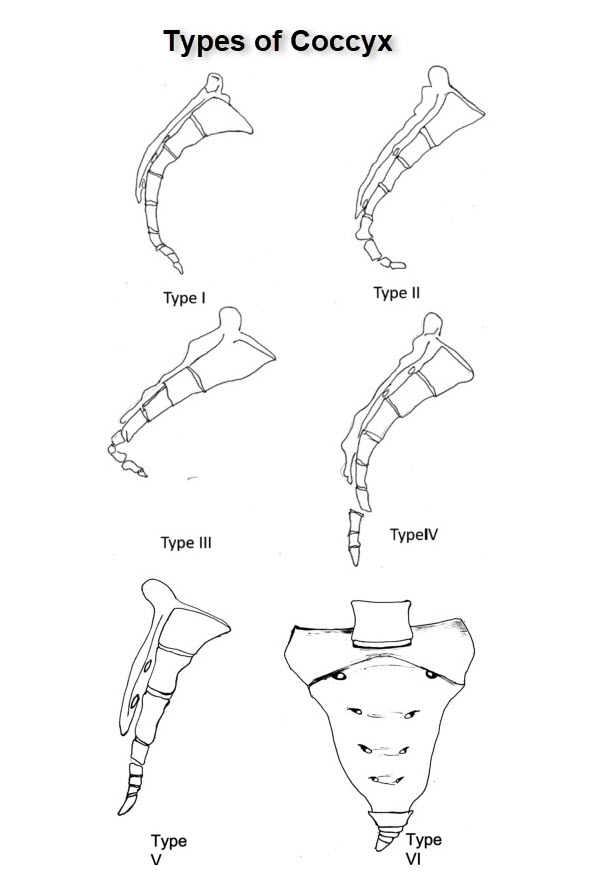

Postacchini and Massobrio described four orientations of the coccyx. Two more types were further added by Nathan et al.

- Type I

- Curved slightly forward, with its apex pointing caudally

- Most common type

- Found in 50% of the people.

- Type II

- Curved more markedly anteriorly

- Apex pointing straight forward

- 8-32% of people.

- Type III

- Sharply angulated forward between the first and second or the second and third segments

- 4-16% of the people

- No subluxation

- Type IV

- The coccyx is subluxed anteriorly at the level of the sacrococcygeal joint or at the level of the first or second intercoccygeal joints

- 1-9%

- Type V

- Retroverted with the posteriorly angulated apex

- 1–11% of the population

- Type VI

- Scoliotic or laterally subluxated coccyx.

- 1–6%

Patients with a type III-VI coccyx were found more commonly in cases with coccydynia.

Image credit: Science Direct

Causes of Coccydynia

Coccydynia occurs if there is an injury or excess pressure on the area causing the bones to move beyond their normal very limited range of motion. This results in inflammation and localized pain. Ligaments, the vestigial and bones of the coccyx can source of pain. Infection of coccyx can also lead to pain.

Following are the common causes of coccydynia

- Trauma- Most common cause

- Injury to coccyx during childbirth

- Horse riding

- Sitting on a hard surface for long periods

- Tumor

- Infection

- Idiopathic

- Coccygeal hypermobility

Female gender and obesity are known risk factors of coccydynia.

Clinical Presentation

A localized pain over the coccyx region that is worse with sitting is the classic presentation of coccydynia.

The pain will usually worsen with

- Prolonged sitting

- Leaning back in a seated position

- Moving from sitting to standing position.

The patient may also complain of pain during sexual intercourse or defecation.

The pain may begin insidiously or following a trauma.

The sitting tolerance or the period for which can be tolerated before the pain forces to change position is enquired.

In females, any events around childbirth become important.

On examination, the coccyx would be tender to touch.

The rectal examination would allow checking for coccyx mobility [sacrococcygeal joint, normal appx 13 degrees.]

The examination includes lumbar spine examination and other probable causes of pain like

- Ischial bursae

- sacroiliac joints

- Lumbosacral facet joints

- Lumbosacral or gluteal muscles.

The skin over the spine should be examined for sinus [pilonidal sinus] and any other notable deformity.

Differential Diagnoses

- Lumbar pain

- Endometriosis

- Hemorrhoids

Diagnostic Workup

Not required for diagnosis except to rule out infection.

Imaging

X-rays

X-ray is an initial investigation especially in patients with a history of trauma. AP and lateral view are most commonly done.

Coned-down view of the coccyx gives better exposure.

X-rays may reveal

- Fractures

- Osteophytes

- Abnormal sacrococcygeal curvature

- Sacrococcygeal or intracoccygeal dislocation.

Dynamic stress films [sitting and standing positions] can detect the sagittal rotation of the pelvis.

CT/ MRI

CT of Coccyx is rarely indicated for objective evidence of fractures in medicolegal cases.

MRI coccyx is usually not required but can be included in the lumbosacral MRI if the pain is thought to originate from anatomic structures located more superiorly within the spine.

CT/MRI can be useful in intrapelvic pathologies.

In a typical case, all imaging studies will be negative.

Injections for Localization of Pain

The injections of local anesthetic with or without steroid can be used for diagnosis of pain source whether it is coccyx or some other structure. If injection to the coccyx results in pain relief, most likely the coccyx is responsible for pain.

These injections can also help identify patients who might benefit from a coccygectomy when contemplated.

Treatment of Coccydynia

A number of coccygeal pains are self-limiting. Most of the coccyx pains can be treated conservatively. In fact, about 90 % of the treatment of coccydynia has the following options.

These are

- Ergonomic Measures

- Posture training

- Cushions – Doughnut or ring-shaped pillows

- Manual or physical therapy

- Manipulation of coccyx and massage of the levator ani (pelvic floor muscles).

- Injections and nerve block – Steroid or anesthetic injections, prolotherapy, and ganglion impar block.

- Surgery – coccygeoplasty or partial or complete coccygectomy.

Most of the patients of coccydynia can be treated by conservative treatment.

Ergonomic Measures

Posture Training

The patient is educated about correct sitting posture and avoid leaning back while sitting. Activities that worsen pain such as prolonged sitting, bike riding, horse riding etc should be avoided.

Activity Modification

Modification of activities takes the pressure off of the tailbone and reduces pain. These include

- Standing desk to avoid prolonged sitting

- Cushion or pillow for coccyx

- Lean forward while sitting to take the weight off the coccyx

Local heat/Cold Application

The patient can apply local heat or cold [both have been found to be equally effective]. The best way to do this is by Sitz bath where water is filled in the tub or Sitz kit [commercially available] and the patient immerses perineum and hip.

Cushions

Cushions help to relieve the pressure of the coccyx.

Modified wedge-shaped cushions or coccygeal cushions which can relieve the pressure on the coccyx when the patient sits are recommended. These are available over the counter.

Local Heat or Cold Application

The patient can apply local heat or cold [both have been found to be equally effective]. The best way to do this is by Sitz bath where water is filled in the tub or Sitz kit [commercially available] and the patient immerses perineum and hip.

Drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to relieve pain and inflammation.

Topical analgesic creams are also used and help to avoid side-effects of oral medications.

Physical Therapy

Pelvic Floor Exercises for Coccydynia

Pelvic floor rehabilitation can be helpful for coccydynia that is associated with pelvic floor muscle spasms.

Tight, painful muscular structures such as the levator ani, coccygeus, or piriformis muscles are targeted. Myofascial release techniques may be used. Local modalities also may be helpful.

Pelvic floor physical therapy has been reported to be an effective treatment for chronic pain including those who have chronic coccydynia even after coccygectomy.

Manual Manipulation and Massage

This refers to intrarectal manipulation under anesthesia. Many authors have claimed it to be mildly effective through clear evidence is lacking.

Injections

Ganglion Blocks

The ganglion impar is also called ganglion of Walther and is the unpaired terminal ganglion of the paravertebral sympathetic nervous system usually located anterior to the sacrococcygeal junction or near.

Hypersensitivity of the ganglion impar is thought to be responsible for persistent chronic pain which is sympathetically maintained.

Local injection of an anesthetic can effectively block the ganglion impar and thereby relieve coccyx pain.

Repeat ganglion impar blocks may be required and have been shown to provide additional benefit.

Steroid Injections

Steroid injections mixed with local anesthetics are given around the coccyx, usually at the sacrococcygeal junction or around the sacrococcygeal ligaments.

Repeat injections may be required.

Invasive Procedures

Nerve Ablation

Nerve ablation uses heat or cold or current to destroy nerve fibers. Nerve ablation in coccyx pain is reserved for patients with chronic pains where none of the treatments has relieved pain [before coccygectomy].

The site of pathology would depend on the specific site of coccygeal pathology. A diagnostic injection of local anesthetic prior to ablation is performed to ascertain the site of pain.

If one sitting of ablation does not provide relief, it may be repeated.

Some patients may have a recurrence of pain after months or years due to collateral reinnervation. A repeat ablation may be performed in such cases.

Surgery for Coccyx Pain

Surgical treatment for coccydynia is partial or complete coccygectomy [removal of coccyx].

Surgical procedures for the treatment of coccydynia are used only as a last resort. The procedure has been associated with a high complication rate.

It is recommended that non-surgical options must be exhausted before considering surgery.

Other Treatments

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or TENS could be of benefit in selected cases.

If a non-organic cause is suspected, psychotherapy is indicated.

References

- Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014 Spring. 14 (1):84-7.

- Kim NH, Suk KS. Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia. Yonsei Med J. 1999 Jun;40(3):215–220.

- Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)2000 Dec 1;25(23):3072–3079.

- Foye PM, Buttaci CJ, Stitik TP, Yonclas PP. Successful injection for coccyx pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Sep;85(9):783–784.

- Buttaci CJ, Foye PM, Stitik TP, et al. Coccydynia successfully treated with ganglion impar blocks: a case series. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Mar 2005. 84(3):218.

- Gopal H, McCrory C. Coccygodynia treated by pulsed radiofrequency treatment to the Ganglion of Impar: a case series. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014 Feb 20.