Last Updated on May 3, 2022

Compartment syndrome is a condition in which there is an increased pressure within a limited space which compromises tissue circulation and function.

Compartment syndromes can be acute, chronic.

Acute compartment syndromes generally occur following a trauma and results in significant elevation of intracompartmental pressures. For example fracture of proximal tibia are frequently associated with compartment syndrome of leg.

Acute compartment syndrome occurs following fractures, vascular injuries or crush injuries.

If not timely identified and intervened, acute compartment syndrome can lead to disastrous consequences.

Chronic compartment syndromes are milder, recurrent, and usually associated with exercise, repetitive training, or exertion.

Compartment syndrome may affect any compartment, including the hand, forearm, upper arm, abdomen, buttock, and entire lower extremity.

The anterior compartment of leg is most common site of compartment syndrome. Tibial fracture is the most common precipitating event.

Long-term sequelae and complications of a missed or delayed diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome can be ominous.

Therefore any suspicion of a compartment syndrome is an indication for obtaining pressure measurements. Timely definitive treatment by decompression reduces the incidence of long-term complications and gives more predictable results.

Pathophysiology of Compartment Syndrome

Image Credit:asahq

The pathophysiology of compartment syndromes following acute trauma, chronic injury or crush injury is similar.

It begins with arterial spasm or contusion resulting in swelling within a fixed space. Artery or venous bleeding directly into the compartment causes may also increase the compartment pressure.

The increase in compartmental pressure constricts intracompartmental veins and raises intravenous pressure.

Due to raised venous pressure, there is a reduction of directly reduces the arterio-venous (A-V) gradient, causing a reduction in arterial blood flow.

This leads to ischemia of the tissues as oxygen requirements of the tissues are no longer met.

When the interstitial pressure exceeds the AV perfusion gradient capillary collapse occurs, worsening the ischemia further.

Image Credit: Hughson

In response, skeletal muscles release histamine-like substances that increase vascular permeability.

This causes the plasma to leak out from the vessels, further raising the interstitial pressure. There is also relative blood sludging in the small capillaries leading to further worsening of the ischemia.

Muscle cells die and decomposed myofibrillar proteins osmotically draw water from arterial blood.

This vicious cycle of worsening tissue perfusion continues to propagate.

However, compartment tamponade occurs as arterial blood flow is occluded

In general, compartmental pressures higher than 30 mm Hg require decompression and if left untreated tissue necrosis, and nerve injury occurs within 6-10 hours.

Cellular destruction and alterations in muscle cell membranes lead to the release of myoglobin into the circulation which can cause renal injury.

Renal failure or sepsis may cause death.

In vascular injury, the mechanism slightly differs. Most cases of compartment syndrome after vascular injury occur with reperfusion which occurs most likely due to ischemic depletion of high-energy phosphate forms and ischemic muscle injury.

It must be noted that the culprit is reduced A-V gradient and tissue perfusion, therefore, it is not necessary for the intracompartmental pressure to be above systolic or diastolic pressure for a compartment syndrome to develop and distal arterial flow may be intact.

Therefore, the presence or absence of peripheral pulses is a poor indicator of compartment syndrome.

Further, digital capillary beds drain into extracompartmental veins and the distal digital A-V gradient and blood flow remain intact.

Therefore, the warmth of the digits, capillary refill, and distal pallor are not reliable indicators either.

In chronic exertional compartment syndrome, repetitive loading or microtrauma related to physical activity are responsible.

Functional impairment in muscles occurs after 2-4 hours of ischemia and irreversible functional loss after 4-12 hours.

Nerve tissue is more sensitive and shows abnormal function after 30 minutes of ischemia. Irreversible functional loss occurs after 12-24 hours.

Causes of Compartment Syndrome

Increased Compartment Content

- Bleeding

- Major vascular injury

- Bleeding disorder

- Anticoagulant therapy

- Increased Capillary Permeability

- Post-ischemic swelling: arterial bypass grafting, embolectomy, ergotamine ingestion, cardiac catheterization, lying on a limb

- Intensive muscle use: exercise, seizures, tetany, eclampsia

- Trauma- fracture, contusion

- Burns

- Intra-arterial drugs

- Orthopedic procedures- osteotomy, fracture reduction & fixation

- Snakebite

- Increased Capillary Pressure

- Exercise

- Venous obstruction – Deep venous thrombosis, Venous ligation

- Ill-fitting brace,

- Muscle hypertrophy

- Intensive muscle use (eg, tetany, vigorous exercise, seizures)

- Everyday exercise activities (eg, stationary bicycle use, horseback riding

- Infiltrated infusion, leaky dialysis cannula

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Popliteal Cyst

Decreased Compartment Size

The reasons for this are mostly iatrogenic

- Closure of fascial Defects

- Tight Dressings, splints, and casts

- Localized external pressure

- Excessive Traction to the fractured limb

- Military antishock trousers

- Lithotomy position

- Intraosseous infusion

- Attempts at cannulating veins and arteries of the arm in patients on systemic anticoagulants

- Intraoperative use of a pressurized pulsatile irrigation system

- Chemotherapy drugs

- Following orthopedic surgeries

- postoperative hematoma

- muscle edema

- tight closure of the deep fascia.

- Leg after coronary artery bypass graft harvesting

Eighty percent of the compartment syndromes in children are secondary to fractures. [Femur (36%), supracondylar humerus (16%), the forearm (16%), and the tibia (9%)]

In adults, major causes of acute compartment syndromes are fractures (45%), soft tissue injury (16%), arterial injury (13%), drug overdose and limb compression (11%), and burns (5%).

Leg, forearm, wrist, and hand and foot are most commonly affected by compartment syndrome.

Anatomy of Compartments in Different Regions

The extremities are made up of intra and extra compartmental spaces formed by fascial attachments to the bone. Each compartment contains muscles, nerves, and arteries enclosed by fascia.

Gluteal

The gluteal region is made up of three compartments: tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius and minimus, and gluteus maximus.

Image credit

A compartment syndrome here would cause the tense region and the buttock and pain with abduction or flexion of the hip .

Iliacus

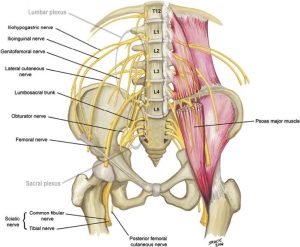

The iliacus compartment lies anterior to the hip and contains the psoas major and minor, and iliacus muscles, the femoral nerve, and the femoral artery.

Image Credit: JBJS Am

The patient may present with saphenous nerve paraesthesia, pain in the inguinal region, femoral nerve palsy and pain with passive hip extension.

Thigh

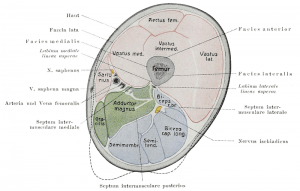

The thigh is said to have two compartments – an anterior compartment and a posterior compartment (which includes the adductor muscles).

Image in public domain

Some authors divide thigh into three compartments namely anterior, a posterior, and a medial or adductor compartment.

The anterior compartment of the thigh contains the quadriceps muscle, the quadratus and sartorius muscles, the femoral nerve and artery. The patient may have pain with flexion of the knee and saphenous nerve dysesthesias along the medial aspect of the leg and foot.

The posterior compartment of the thigh contains the biceps femoris, semimembranosus, semitendinosis, and sciatic nerve, and the deep femoral artery. The medial or adductor compartment of the thigh contains the adductor muscles and the obturator nerve.

Leg

The leg has anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior compartments.

Image Credit: hughston

Anterior compartment is formed by tibia, fibula, interosseous membrane and anterior intermuscular septum.

It contains the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus, and peroneus tertius muscles, the deep peroneal nerve, and the anterior tibial artery. Clinically, the patient may present with tenseness and tenderness anteriorly, pain with passive toe extension, sensory loss in the first web space. Dorsalis pedis pulse is usually present. The anterior compartment is the most common location for compartment syndrome.

The lateral compartment is formed by an anterior intermuscular septum, fibula, posterior intermuscular septum and deep fascia. It contains the peroneus longus and peroneus brevis muscles, the deep and superficial peroneal nerves, and the peroneal artery. Patients with this affected compartment have weak eversion of the foot and decreased sensation on the dorsum of the foot.

Lateral compartment involvement is the second most frequent compartment syndrome and is often associated with anterior leg compartment syndromes.

The superficial posterior compartment of the leg contains the gastroc-soleus complex, the plantaris muscle, and the sural nerve. It is surrounded by the deep fascia of the leg. The patient has decreased sensation on the lateral aspect of the foot. It is lease frequently involved compartment.

The deep posterior compartment is formed by tibia, fibula, deep transverse fascia and interosseous membrane. It contains the tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, and flexor digitorum longus muscles, the tibial artery, and the tibial nerve. The patient may have diminished sensation on the plantar aspect of the foot. The posterior tibial pulse is usually present.

The tibialis posterior compartment is a more recently described subdivision of the deep posterior compartment. It consists of the tibialis posterior, which has been shown to have its own fascial layer.

Foot

Image Credit: AO

The foot is composed of eight compartments – superficial, deep medial, lateral, and four interossei.

The medial compartment of the foot contains the intrinsic muscles of the great toe, excluding the adductor hallucis. .

The lateral compartment of the foot contains the flexor digiti minimi and abductor digiti minimi muscles.

The central compartment of the foot contains the adductor hallucis and quadratus plantae muscles, and the flexor digitorum longus, flexor digitorum brevis, and flexor hallucis longus tendons

The four web spaces make up the interossei compartments and contain the interosseous muscles, the digital nerves, and plantar arteries.

Arm

Lateral and medial intermuscular septum divides the arm into an anterior and posterior compartment.

The anterior compartment or flexor compartment of the arm contains the biceps brachii, the brachialis, and the coracobrachialis.

The posterior compartment or extensor compartment contains the triceps brachii and anconeus muscle.

Forearm

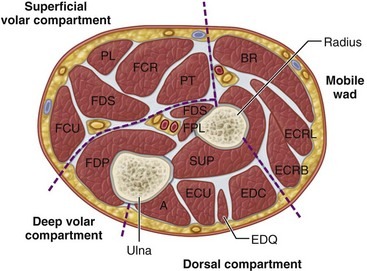

The forearm is divided into interconnected superficial volar (flexor), deep volar, dorsal (extensor) compartment and a compartment containing the mobile wad of Henry.

Image Credit: Clinical Gate

The deep volar compartment contains the flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus muscles and tendons.

The mobile wad of Henry has the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis brevis, and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles and tendons.

Dorsal compartment contains extensor muscles.

Elevated pressures most commonly affect the volar compartments, but the dorsal and mobile wad compartments may also be involved.

Clinically, it is difficult to differentiate between isolated or combined involvement.

Wrist

Volar wrist tendons, for the most part, are tightly constrained within the carpal tunnel except for the flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus tendons, which are in separate compartments. The dorsal compartments are primary channels for tendons and are rarely afflicted by compartment syndrome.

The dorsal extensor tendons pass under an extensor retinaculum and are divided into 6 compartments.

Hand

Image Credit: Clinical Gate

The hand has 10 compartments

- Dorsal interossei (4 compartments)

- Palmar interossei (3 compartments)

- Adductor pollicis compartment

- Thenar compartment

- Hypothenar compartment

Clinical Presentation of Compartment Syndrome

The possibility of a compartment syndrome should be considered in all significant injuries. Patients who are uncooperative, unresponsive, or unreliable, intoxicated, overdosed, having a neurologic disease, or not alert should be monitored very closely for compartment syndrome.

The chief complaint is pain disproportionate to the injury.

Pain is deep, aching and burning. It is worsened by passive stretching of the involved muscles. There may a tense feeling in the extremity.

Another complaint is paresthesia [ It is not a reliable complaint though. A decreased 2-point discrimination is a more reliable early test but requires conscious, awake and cooperative patient]

High-velocity injuries causing fractures, penetrating injuries causing vascular injury [arterial or venous] are more prone to compartment syndrome.

Anticoagulation therapy and bleeding disorders (eg, hemophilia) significantly increase the likelihood of compartment syndrome.

Vigorous exertion in soldiers and athletes may also cause compartment syndrome. In case of suspicion, intracompartmental pressure should be checked even in the absence of any trauma history.

Compartment syndrome in the hand most often occurs following iatrogenic injury in a patient in ICU and high index of suspicion is required.

On examination, the limb can be compared to contralateral limb.

Following findings may be noted

- Tightness and swelling

- Pain with movements especially passive stretching of the muscles [Earliest clinical indicator but not very reliable]

- Decreased two-point discrimination in the affected nerve distribution

- Firm, wooden or stony feeling on deep palpation [Most important clinical finding]

- Presence of blisters [they can occur without compartment syndrome too]

- The traditional 5 P’s of acute ischemia in a limb pain, paresthesia, pallor, pulselessness, poikilothermia [ not very reliable as they manifest very late]. Nowadays the sixth P is added – which means increased pressure of compartment as palpated by tense/woody feel.

- Decrease peripheral pulses and capillary refill [ remain normal in most cases of upper extremity acute compartment syndrome.]

To evaluate a patient of suspected compartment syndrome, when a patient complains of pain, determine whether any neural compromise is present as the sensory nerves tend to be affected before the motor nerves.

Look for decreased 2-point discrimination which is the most consistent early finding, and diminished vibration sense as measured with a 256 cycle per second tuning fork

[Pulses are unreliable and by the time pulses disappear, the syndrome is far advanced.]

Differential Diagnoses

- Cellulitis

- Deep Venous Thrombosis

- Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections

- Gas Gangrene

- Peripheral Vascular Injuries

- Rhabdomyolysis

Diagnosis of Compartment Syndrome

Laboratory results are often normal and are not necessary to diagnose compartment syndrome. Moreover, they are not able to rule out compartment syndrome.

In acute compartment, though there is a concern for rhabdomyolysis which occurs due to increased destruction of muscle tissue.

So following workup may be done

- Serum creatine phosphokinase

- normal – 130 IU

- Acute compartment syndrome – 1000 to 5000 IU

- Crush syndrome > 100,000 IU

- White blood cell count

- Serum

- Potassium

- Renal function tests

- Creatinine

- Blood Urea Nitrogen

- SGOT, and LDH.

- Urine for myoglobin

Measurement of intracompartmental pressures remains the standard for diagnosis of compartment syndrome. This procedure should be performed as soon as a diagnosis of compartment syndrome is suspected.

Per se imaging studies are not helpful in making the diagnosis of compartment syndrome but help to gauge the underlying bony injuries.

X-rays are primary imaging modality. CT can be done for more complex fractures.

Muscle tears can be observed using MRI or ultrasonography.

In suspected vascular injury, Doppler ultrasound may be done. Angiography can also be done in vascular injury.

Compartment Pressure Measurement

Various methods and equipment can be used for compartment pressure measurement. A transducer connected to a catheter usually is introduced into the compartment to be measured. This is the most accurate method of measuring compartment pressure and diagnosing compartment syndrome.

Commercial tonometers are available for pressure measurement of the compartment.

In chronic compartment cases, measurement of the compartment pressure then can be performed at rest, as well as during and after exercise.

Pressure measurement is, nonetheless the most accurate diagnostic test in a patient with suspected compartment syndrome.

The normal intracompartmental pressure is between 0 and 8 mmHg

With the acute syndrome, the exact pressure threshold is controversial, but typical ranges are from 30-45 mm Hg at rest. Some sources state that it is better to associate this pressure to diastolic pressure (that is, within 10-30 mm Hg of diastolic pressure).

Treatment of Compartmental Syndrome

Muscle has considerable ability to regenerate by forming new muscle cells. Therefore, it is extremely important to decompress ischemic muscle as early as possible. Compartment pressures return to normal after a fasciotomy.

Analgesics can be used for management of pain.

Immediate Measures when compartment syndrome is developing

- Remove all tight envelopes

- Bivalve the cast

- Remove the dressings

- Remove cotton wrappings

- Place the extremity at heart level. Do not elevate as that leads to a decrease in arterial circulation

- Fluid management for management of dehydration

- In the case of leg injury, immobilize in slight plantar flexion to decrease posterior compartmental pressure

If the intracompartmental pressure is still elevated and clinical symptoms persist, surgical decompression and fasciotomy of the compartment is indicated.

During fasciotomy, nonviable tissue is debrided. Skeletal fixation and vascular repair should be done after fasciotomy.

Following fasciotomy, fracture reduction or stabilization and vascular repair can be performed, if needed.

Other measures as required should be done. For example in case of snakebite administration of antivenin may reverse a developing compartment syndrome. Correct hypoperfusion with a crystalloid solution and blood products.

Renal functions should be monitored throughout and measures should be taken to keep urine output at 1-2 mL/kg/hr if rhabdomyolysis develops.

This involves alkalization of the urine and diuresis.

Fasciotomy

No consensus exists regarding the exact pressure at which fasciotomy should be performed but it is agreed upon that when compartment pressures are elevated, especially in acute settings, surgical treatment is preferred over monitoring as prolonged elevated pressures can, over a prolonged period can cause irreversible damage.

If the compartment pressure is greater than 40 mm Hg, a fasciotomy is usually performed emergently.

Fasciotomy is indicated if the pressure remains 30-40 mm Hg for longer than 4 hours. As a rule, when in doubt, the compartment should be released.

With compartment syndrome in the hand, surgeons should have a lower threshold for decompression; a compartmental pressure of greater than 15-20 mm Hg is a relative indication for release.

In case of compartment syndrome is diagnosed late, fasciotomy is of no benefit.

Fasciotomy is contraindicated after the third or fourth day following the onset of compartment syndrome. This is because, in such cases, severe infection usually develops in already necrotic muscle. But the compartment is not open, it can heal with scar tissue to result in more functional extremity with fewer complications.

In case the duration is not clear, compartments may be decompressed.

In cases of vascular injury, a fasciotomy should be performed on high-risk patients before arterial exploration.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy helps the patient to regain function. The protocol of physiotherapy would be guided by associated injuries. It involves a range of motion and flexibility exercises.

Once the patient is ambulated, he is put on graduated resistive exercises. Swimming, pedal exercises, water jogging, and running help athletes regain muscle strength and flexibility without loading the affected compartment.

Complications

- Infection

- Renal failure or multiple organ failure

- Permanent muscle and nerve damage

- Chronic neuropathic pain.

- Hypesthesia and painful dysesthesia

Prognosis

The outcome of compartment syndrome depends on both the diagnosis and the time from injury to intervention.

- Within 6 hours – complete recovery

- Within 12 hours – normal limb function in 68% of patients.

- >12 hours or longer – only 8% of patients had normal function.

Recurrent compartment syndrome has been reported in athletes. It is thought to be related to severe scarring and the subsequent closing of the initial compartment release.

Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome has a similar pathophysiology but is unique however in that the symptoms [though may progress to an acute compartment syndrome] are commonly recurrent and associated with exercise.

Some patients who have had previous lower extremity trauma may develop chronic exertional compartment syndrome.

It is most commonly seen in distance runners but may be seen in swimmers, or heavy workers and military recruits.

Calf is most commonly involved. It is known by various other names like exertional compartment syndrome, exercise-induced leg pain, recurrent compartment syndrome, anterior tibial syndrome etc.

The exact cause of chronic exertional compartment syndrome is not known but is probably associated with both limited compartment size due to thickened fascia and the increased volume of compartment contents.

Increased volume may be secondary to muscle hypertrophy, restricted venous outflow, hemorrhage from torn muscle fibers or muscle swelling due to increased capillary permeability and intracellular edema.

Diagnosis can be reached at only after detailed clinical and laboratory investigations.

Pre and post exercise intracompartment pressure assessments often clinch the diagnosis.

Intramuscular pressures measuring greater than 10 mmHg at rest or greater than 25 mm Hg five minutes after exercise are considered to be abnormally elevated. Comparison of pre and post exercise intracompartmental pressures to the uninvolved side may also be helpful.

The treatment includes decreasing the frequency and duration of stressful activities, stretching the involved compartment, orthotics, better hydration, NSAIDs and use of ice after the activity.

If the symptoms are not relieved by six months, surgical fasciotomy may be considered.

References

- Fronek J, et al: Management of Chronic Exertional Anterior Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Extremity. Clin Orthop 220:221-227, 1987.

- . Mubarak S.J.and A.R. Hargens. Acute Compartment Syndromes. Surg Clin N Am 63:539-65,1983.

- Rorabeck, C.H., P.J. Fowler, and P. Nott The Results of Fasciotomy in the Management of Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome. Am J Sports Med 16: 224-227, 1988.

- Matsen FA 3rd. Compartmental syndrome. A unified concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975 Nov-Dec. 8-14.

- Amendala A, Rorabeck CH. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome. Welsh RP, Shepard RJ, eds. Current Therapy in Sports Medicine. 1985. Toronto, Canada: BC Decker; 250-2.

- Clayton JM, Hayes AC, Barnes RW. Tissue pressure and perfusion in the compartment syndrome. J Surg Res. 1977 Apr. 22(4):333-9.

- Rafiq I, Anderson DJ. Acute rhabdomyolysis following acute compartment syndrome of upper arm. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006 Nov. 16(11):734-5.

- Rorabeck CH, Macnab I. The pathophysiology of the anterior tibial compartmental syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975 Nov-Dec. 52-7.

- Jones WG 2nd, Perry MO, Bush HL Jr. Changes in tibial venous blood flow in the evolving compartment syndrome. Arch Surg. 1989 Jul. 124(7):801-4

- Bible JE, McClure DJ, Mir HR. Analysis of One vs. Two-Incision Fasciotomy for Tibial Fractures with Acute Compartment Syndrome. J Orthop Trauma. 2013 Apr 19.

- Hutchinson MR, Ireland ML. Common compartment syndromes in athletes. Treatment and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1994 Mar. 17(3):200-8.