Last Updated on September 17, 2019

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common peripheral nerve entrapment syndrome in the human body. It is the cause of considerable pain and disability for patients.

When appropriately diagnosed, this condition may be treated by both conservative and operative means. In this review, the current thinking on this important and common condition is discussed The recent literature on cubital tunnel syndrome was reviewed, and key papers on upper limb and hand surgery were discussed with colleagues.

Cubital tunnel syndrome is ulnar nerve entrapment neuropathy in the cubital tunnel at the elbow. It is the second most common peripheral nerve entrapment neuropathy in the upper limb.

The cubital tunnel is a space of the dorsal medial elbow which allows passage of the ulnar nerve around the elbow. [see anatomy below]

Relevant Anatomy

Cubital tunnel Formed medially by the medial epicondyle of the humerus, laterally by the olecranon process of the ulna and the tendinous arch joining the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

The roof of the cubital tunnel cubital tunnel retinaculum which is also known as the epicondylo-olecranon ligament or Osborne band). the floor of the tunnel is formed by the capsule and the posterior band of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow joint

Along with other structures, the cubital tunnel contains ulnar nerve. Compression of the ulnar nerve in this tunnel causes cubital tunnel syndrome.

[Read anatomy of Ulnar Nerve]

The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus, and contains fibers from the C8 and T1 spinal nerve roots. It descends the arm just anterior to the medial intermuscular septum and later pierces this septum in the final third of its length. Progressing underneath the septum and adjacent to the triceps muscle, it traverses the cubital tunnel to enter the forearm where it passes between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.

This anatomical arrangement has two implications for the nerve As it lies some distance from the axis of rotation of the elbow joint, movement of the elbow, therefore, requires the nerve to both stretches and slide through the cubital tunnel. Sliding has the greatest role in this process, although the nerve itself can stretch by up to 5 mm.

There is an increase in intraneural pressure with elbow flexion. I addition, the shape of the elbow becomes oval to elipse, narrowing canal by 55%.

Wrist extension and shoulder abduction are further known to increase the intraneural pressure.

Risk Factors for Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

- Diabetes mellitus

- Works involving long periods of elbow flexion

- Post-trauma

- Marked varus or valgus deformity at the elbow.

- Obesity

- Workers operating vibrating tools

- Bone spurs/ arthritis of the elbow

- Swelling of the elbow joint

- Cysts near the elbow joint

Pathophysiology of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Compression, traction, and friction have been implicated in cubital tunnel syndrome.

Compression is the principal mechanism. It could be mechanical compression to the nerve substance or by compression of the intrinsic blood supply leading to ischemia.

Previous injuries to the nerve, a tight tunnel may predispose the nerve to friction and compression. Diabetes may make a nerve more vulnerable to compression by causing local ischemia or by interfering with nerve metabolism.

Clinical Presentation of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

- Altered sensation in the little and ring fingers.

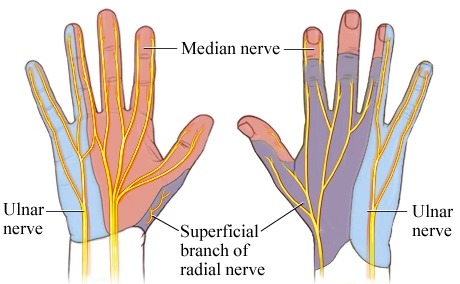

- Sensory loss in the distribution

- Clumsiness in the hand with the progression of the severity.

- Wasting of hypothenar muscles, small muscles of the hand and muscles on the ulnar side of the forearm.

The examination may show Froment’s sign which refers to overt clawing of the ulnar innervated digits (usually the little and ring fingers).

There could be the abduction of the little finger (Wartenberg’s sign).

Elbow may show a valgus deformity, possibly secondary to a previous fracture. [The palsy is called tardy ulnar palsy]

Elbow otherwise, may be normal.

Tinel’s sign should be positive over the cubital tunnel.

It must be noted that compression in Guyon’s canal, which also causes ulnar nerve symptoms, the sensation is preserved over the dorsum of the hand because of the dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve that comes off proximal to Guyon’s canal.

McGowan Score

It grades the ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Mild occasional paraesthesia, positive Tinel’s sign, subjective weakness

- Moderate paraesthesia, objective weakness, positive Tinel’s sign

- Severe constant paraesthesia, weakness, overt muscle wasting

The elbow flexion test is a useful accurate provocative test for cubital tunnel syndrome.

Differential Diagnoses

- Ulnar neuropathy at other places

- Brachial plexus injury

Investigations

The diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome is mainly clinical. The nerve conduction studies can be done to confirm the diagnosis.

In mild cases though, may have normal nerve conduction studies.

X-rays of elbow could be done to rule out bony changes. X-rays may reveal osteoarthritis, cubitus valgus or calcification in the medial collateral ligament.

Treatment

Conservative treatment consists of avoiding provocative activities, NSAIDs, and brace to check elbow flexion.

Mild cases of mild cases of cubital tunnel syndrome may resolve spontaneously

Surgery is done in severe cases, and where conservative management fails.

Surgical treatment consists of decompression to remove the compression. Some surgeons prefer just the release whereas others also transpose the nerve anteriorly out of the cubital tunnel.

Medial epicondylectomy may rarely be needed.

Complications of ulnar nerve release

- Persistent dysaesthesia

- Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

- Infection

- Neuroma formation

- Persistent sensory deficit and weakness

References

- Descatha A, Leclerc A, Chastang J F. et all incidence of ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow in repetitive work. Scand J Work Environ Health 200430234–240

- Buehler M J, Thayer D T. The elbow flexion test. A clinical test for the cubital tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998233213–216.

- Padua L, Aprile I, Caliandro P. et al. Natural history of ulnar entrapment at the elbow. Clin Neurophysiol 20021131980–1984.

- Matsuzaki H, Yoshizu T, Maki Y. et. A long-term clinical and neurologic recovery in the hand after surgery for severe cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg [Am] 200429373–378.