Last Updated on October 29, 2023

This gives the limb an overall the appearance of an archer’s bow.

This condition may present from infancy through adulthood and has a variety of causes.

The problem may be unilateral which would result in functional leg length discrepancy or bilateral.

It is interesting to note that almost all babies are born bow-legged. By the time babies begin to walk, the leg bones get straightened to allow walking.

Physiologic genu varum is defined as occurring in children younger than 2 years. It is symmetrical and painless bowing, usually associated with in-toeing and often with a propensity for tripping. This problem will correct spontaneously with normal growth.

Genu varum is more common when nutrition is poor and incidence of genu varum is higher in countries where malnutrition is prevalent.

Pathophysiology of Genu Varum

In normal alignment, the lower-extremity lengths are equal, and the mechanical axis (center of gravity) bisects the knee when the patient is standing erect with the patellae facing forward.

This places a relatively balanced load on the medial and lateral compartments of the knee and on the collateral ligaments. This keeps patella stable and centered in the femoral sulcus.

Genu varum is defined by medial displacement of the mechanical axis

When axis shifts medially, the medial femoral condyle and the medial plateau of the tibia are subjected to pathologic loading. The loading leads to compression of the physis [ Heuter-Volkmann effect ] and this leading to inhibition of the normal ossification of the epiphysis.

There occurs stretching of the lateral collateral ligaments. Severe deformity leads to greater stretching and the knee pain and lateral thrust during the gait, characteristic in-toeing. The patient ultimately walks with a waddling gait.

During the adulthood, eccentric stress on the knee may result in medial meniscal tears, tibiofemoral subluxation, articular cartilage attrition, and arthrosis of the medial compartment of the knee.

Causes of Genu varum

- Tibia vara (Blount disease)

- Infantile

- Juvenile

- Adolescent

- Rickets

- Nutritional

- Hypophosphatemic

- Renal disease

- Skeletal Dysplasias

- Achondroplasia

- Pseudoachondroplasia

- Multiple epiphyseal dysplasias

- Metaphyseal dysplasia

- Celiac sprue and other digestive disorders

- Tibia vara (Blount disease) is a growth disturbance

Clinical Presentation of Genu Varum

The parents generally bring the child with concerns of noticeable deformity and/or awkward gait. The examination would reveal a unilateral or bilateral nature of the problem.

It is most helpful to observe the child in a standing position with feet together and with equal weight on both legs.

Intercondylar distance measurement would provide a rough idea.

Observe the gait noting the foot progression angle and the presence or absence of a lateral thrust.

In the prone position, measure the inward-outward hip rotation (for femoral torsion) and the thigh-foot axis (for tibial torsion).

In addition, examine the entire spine and hip of the child.

They may also have ankle varus with medial thigh and calf creases.

Lab Studies

When an underlying syndrome is suggested by the physical findings and history, the appropriate genetic workup is warranted. Relevant hematologic and urine studies should be done in suspected cases.

Bone densitometry studies can be done in selected cases.

Imaging

X-ray

Full-length weight-bearing anteroposterior view of the lower limbs is the gold standard which would reveal the deformities very well.

An x-ray would reveal whether the deformity is in the proximal tibia or distal femur.

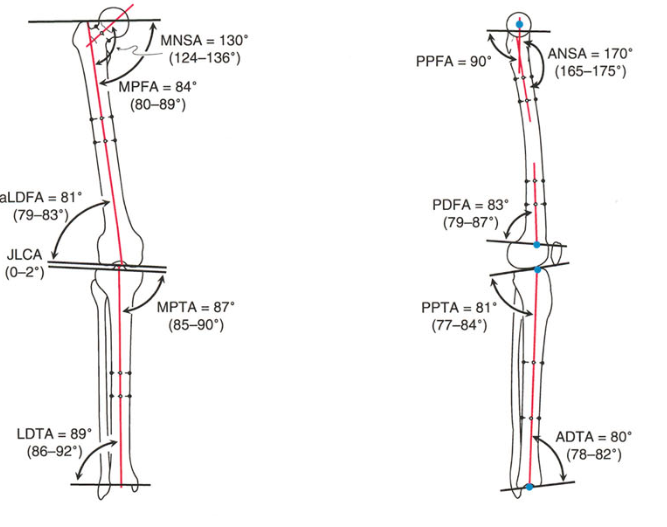

Measurement of the anatomic joint-shaft angles at each level would help to localize the problem.

Lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA) is formed between the axis of the femur and the femoral joint line. It is normally 84°.

See normal alignment angles below.

Proximal medial tibial angle (PMTA) is formed between the axis of the tibia and upper tibia and is normally 87 degrees.

Alteration of values would demonstrate whether the issue is with the tibia or femur.

Stress radiographs may demonstrate lateral ligaments incompetency.

Sagittal-plane and rotational deformities may confound the analysis and should be taken into account as well.

CT/MRI

Unless a physeal bar is suspected (which is unusual), there is no need to resort to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Treatment of Genu Varum

Bracing, once popular is ineffective. Osteotomy is effective but the procedure is permanent, therefore needs to be astutely timed to the remaining growth potential which often becomes difficult.

Guided growth is a minimally invasive and offers the advantage of being a temporary stoppage to growth and reversible nature. Staples and percutaneous transphyseal screw were in vogue earlier but now the preference is to use eight-plate which is fixed by two screws above and below physis.

Guided growth is the treatment of choice in growing years. It may be needed to be repeated though.

After skeletal maturity has been reached, corrective osteotomies may be required to correct a malalignment.

Non-operative Treatment

For physiologic genu varum, parental reassurance is required. In borderline cases, continued follow-up is warranted.

In nutritional or metabolic rickets, medical treatment has a prime role. In case of nutritional rickets, correction of deformity can be achieved by supplementation of vitamin D and calcium.

Dietary management for celiac sprue, administration of bisphosphonates in select cases of osteopenia, and gene therapy for collagen storage disorders are examples of some other measures.

Operative Treatment

Guided Growth

The idea is to stop the growth of lateral hemiphysis so that by continued growth on medial hemiphysis, the limb gets straightened. Whether it is to be done in the tibia or femur is decided by the severity of deformity and involvement.

In advanced cases, both the femur and the tibia/fibula may have to be addressed.

Eight plate is known because of its shape resembling ‘8’ number. It spans and fixes the physis, not allowing it to grow, held by two screws on each side of physis. After correction, the plate is removed to allow the growth. If needed the procedure may be repeated.

Physiologic deformity and physeal closure are contraindications to guided growth surgery.

Staples and screws, once popular are on a decline due to the higher number of complications.

The goal of guided growth is to restore the mechanical axis to neutral.

The time to correction ranges from 6 to 24 months.

Osteotomy

It needs to be considered when either there is already skeletal maturity or there is not enough growth potential left for use of guided growth.

The goal of osteotomy is to realign the extremity and provide a neutral mechanical axis while correcting malrotation and restoring equal limb lengths.

Complications of Procedure

- Premature physeal closure

- Rebound growth

- Overcorrection

- Infection

- Plate breakage

- Screw migration

- Screw breakage

References

- Kulkarni RM, Ilyas Rushnaiwala FM, Kulkarni GS, Negandhi R, Kulkarni MG, Kulkarni SG. Correction of coronal plane deformities around the knee using a tension band plate in children younger than 10 years. Indian J Orthop. 2015 Mar-Apr. 49 (2):208-18.

- Steel HH, Sandrow RE, Sullivan PD. Complications of tibial osteotomy in children for genu varum or valgum. Evidence that neurological changes are due to ischemia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971 Dec. 53(8):1629-35

- Ogilvie JW. Epiphysiodesis: evaluation of a new technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 1986 Mar-Apr. 6(2):147-9. [Medline].

- Stevens PM. Guided growth for angular correction: a preliminary series using a tension band plate. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007 Apr-May. 27(3):253-9.

- Jelinek EM, Bittersohl B, Martiny F, Scharfstädt A, Krauspe R, Westhoff B. The 8-plate versus physeal stapling for temporary hemiepiphyseodesis correcting genu valgum and genu varum: a retrospective analysis of thirty-five patients. Int Orthop. 2012 Mar. 36 (3):599-605.

- Novais E, Stevens PM. Hypophosphatemic rickets: the role of hemiepiphysiodesis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006 Mar-Apr. 26(2):238-44