Last Updated on October 29, 2023

Legg Calve Perthes disease is an idiopathic avascular necrosis of the proximal femoral epiphysis in children resulting from compromise of the tenuous blood supply to this area.

Legg Calve Perthes disease usually occurs in children aged 4-10 years. Mean age is 7 years. Mostly, the disorder is unilateral.

It affects 1 in 10,000 children with a male to female ratio being 5:1. The disease is more commonly seen in less densely populated areas and lower socioeconomic class

Both hips are involved in fewer than 10% of cases in a successive manner. That means both hips are never at the same stage of disease)

The condition is also known by names like coxa plana, Legg-Perthes’ disease, Perthes disease, osteochondritis deformans coxa juvenilis, and pseudocoxalgia.

Risk factors

Risk factors for Legg Calve Perthes disease are

- Positive family history

- Low birth weight

- Abnormal birth presentation

- Second-hand smoke

- Asian, and Central European descent

Pathophysiology of Legg Calve Perthes Disease

The cause is not yet established but appears to be multifactorial. Following factors could be responsible

Disruption in Blood Supply

- Disruption in vascular supply with subsequent revascularization

- Thrombophilia has been reported to be present in 50% of patients

Trauma/Overload (multiple-infarction theory)

- Repetitive trauma or overload

- Epiphyseal bone resorption, collapse, and the effect of subsequent repair

Basically, there is a compromise of the blood supply of the secondary ossification centers in the epiphyses, resulting in necrosis, removal of the necrotic tissue, and its replacement with new bone.

Sometimes the bone replacement is complete resulting in normal bone.

The adequacy of bone replacement depends on

- Age of the patient

- Presence of associated infection

- Joint congruity and other physiomechanical factors.

Children with Legg Calve Perthes Disease have been noted to have following associations

- Maternal active/ passive smoking

- ADHD [33%]

- Delayed bone age [noted in about 90%]

- Disproportionate growth

- Mild shortening of the stature

Legg Calve Perthes disease can also result in following conditions of the hip

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- Trauma

- Steroid use

- Sickle-cell crisis

- Congenital dislocation of the hip.

Pathological Changes Observed in Legg Calve Perthes Disease

Normally, the growth plate receives its nutrition from vessels on its epiphyseal side. Interruption of these vessels causes infarction with necrosis of the proliferative zone of the growth plate.

Ossification of the metaphysis is interrupted and so the plate becomes thinner. Metaphyseal changes of widening and ‘cyst’ formation are seen commonly.

Bone resorption and trabecular fragmentation is seen in the apex of the head.

The articular cartilage shows increased thickness early in the disease because the deeper layer which ultimately forms the epiphyseal bone is deprived of its nutrition. The superficial layer, nourished from the synovial fluid, remains alive and thus appears relatively thick. The death of this deepest zone is not usually complete because recovery occurs and the head continues to grow subsequently.

Changes in adjoining structures

Neck of the femur

- Deformity of the neck can develop very early in the disease

- Upper part of the neck is expanded

- Metaphyseal end becomes rounded off.

- Shortening

Acetabulum

- Increased distance between the medial pole of the head and the floor of the socket.

- Shadows of the head and the ischial bone longer leave a gap between them

- Ligamentum is swollen and congested.

- Acetabular floor loses the usual contour and adapts to the shape of the head. It is a late sign

Classification of Legg-Calves-Perthes Disease

Waldenström Stages

Initial

- Infarction produces a smaller, sclerotic epiphysis with medial joint space widening

- Radiographs may remain normal for 3 to 6 mos

Fragmentation

- Femoral head appears to fragment or dissolve

- Revascularization process and bone resorption produces collapse and subsequent increased density

- Hip related symptoms are most prevalent

- Herring’s Lateral pillar classification based on this stage

Reossification

- Ossific nucleus undergoes reossification as new bone appears as necrotic bone is resorbed

- May last up to 18 months

Healing or remodeling

- Femoral head remodels until skeletal maturity

- Begins once ossific nucleus is completely reossified trabecular patterns returns

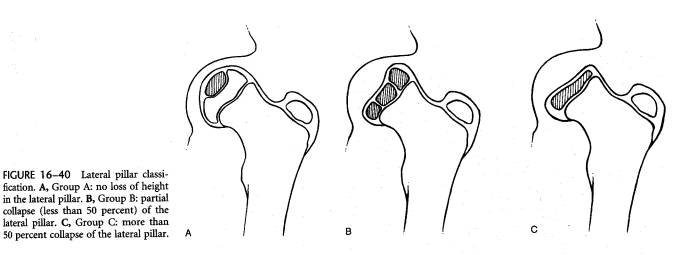

Lateral Pillar Classification of Herring

Determined at the beginning of the fragmentation stage usually after 6 months after the onset of symptoms. It is based on the height of the lateral pillar of the capital femoral epiphysis on AP view of x-ray of the pelvis. It has the best interobserver agreement and provides good prognostic information.

However, the classification is limited to the fragmentation stage and cannot be applied in a patient who is yet to enter the stage of fragmentation.

A

- Lateral pillar maintains full height

- No density changes identified

- uniformly good outcome

B

- >50% height

- Poor outcome in the patient of age > 6 years

B/C Border

- Lateral pillar is narrowed (2-3mm)

- or poorly ossified with approximately 50% height

Group C

- <50% of lateral pillar height is maintained

- poor outcome

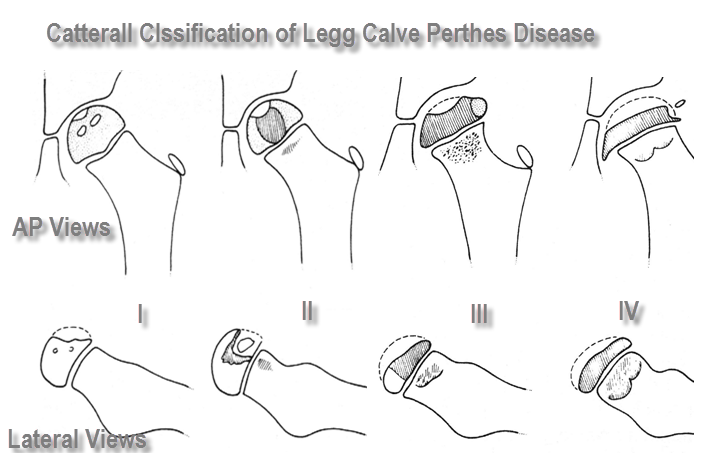

Catterall Classification

It is based on the degree of head involvement as seen on x-ray

I

Involvement of the anterior epiphysis only

II

Involvement of the anterior epiphysis with a clear sequestrum

III

Only a small part of the epiphysis is not involved

IV

Total head involvement

Head at-risk signs

These indicate a more severe course of the disease

- Gage sign

- V-shaped radiolucency in the lateral portion of the epiphysis and/or adjacent metaphysis

- Calcification lateral to the epiphysis

- Lateral subluxation of the femoral head

- Horizontal proximal femoral physis

- Metaphyseal cyst

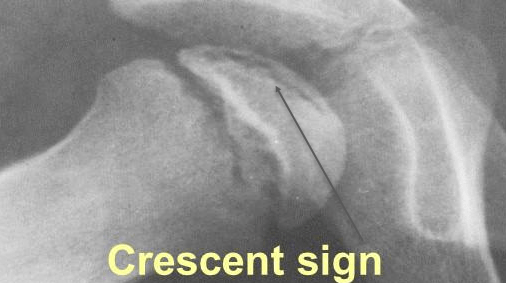

Salter-Thompson classification

It is based on the radiographic crescent sign [which represent a fracture]

A

- Crescent sign involves < 1/2 of the femoral head

B

- Crescent sign involves > 1/2 of femoral head [as in the picture above]

Clinical Presentation of Legg Calve Perthes Disease

The earliest sign of Legg Calve Perthes disease is limp, also called abductor lurch, especially after exertion. The limp could be painless or there could be mild or intermittent pain in the anterior part of the thigh.

There may intermittent period without limp. The pain sometimes may be felt in the knee also.

Sometimes the patients are discovered incidentally at x-ray examination for some other reason.

On examination, the hip motion is limited. Internal rotation is often markedly limited. It is accompanied by hip flexion contracture.

There is sometimes tenderness, both anteriorly and posteriorly over the hip joint area.

Thigh may reveal atrophy, and buttock atrophy may be apparent.

Limb length discrepancy is a late finding.

Differential Diagnoses

- osteomyelitis

- pyogenic arthritis

- Transient synovitis

- Psoas abscess

- juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- hemophilia

- slipped capital femoral epiphysis

Radiographic differential diagnosis

- multiple epiphyseal dysplasia

- spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia

- sickle cell disease

- Gaucher disease

- hypothyroidism

- Meyers dysplasia

Laboratory Studies

- Complete blood count

- Differential and measurement

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Findings may be normal.

Imaging

X-rays

AP of pelvis and frog leg laterals

Early findings [1-2 weeks]

- Effusion of the joint

- medial joint space widening

- Metaphyseal demineralization (decreased bone density around the joint),

- Periarticular swelling (bulging capsule).

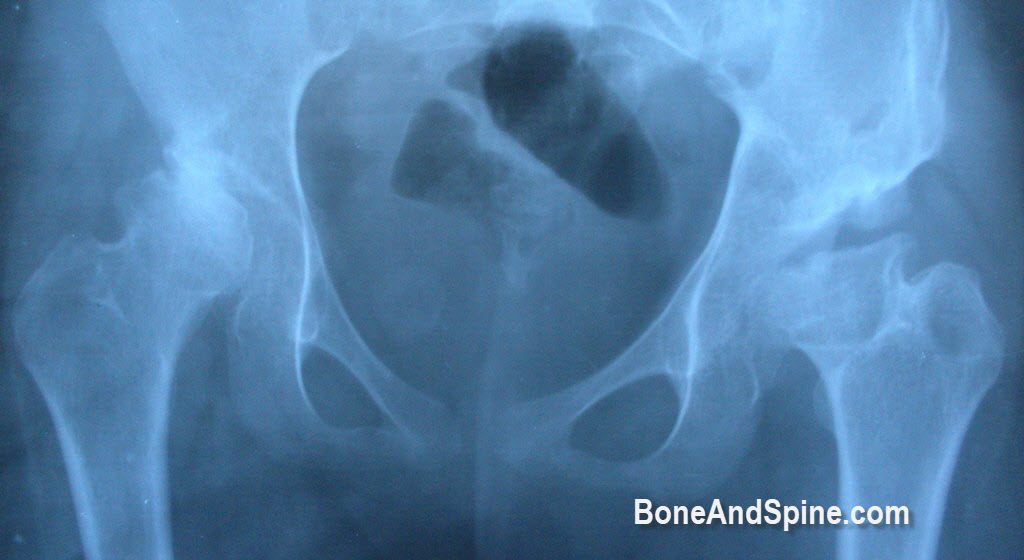

Advanced Disease [3-8 weeks]

- the joint space between the ossified head and acetabulum widens

- Narrowing or collapse of the femoral head causes it to appear widened and flattened (coxa plana).

- Varus deformity of the femoral neck

- Damage to the femoral head growth center

- Overgrowth of the greater trochanteric apophysis.

- the irregularity of femoral head ossification

- Crescent sign (represents a subchondral fracture)

Late Signs [12-40 months]

- Collapse of the femoral head

- Increase in the width of the neck,

- demineralization of the femoral head. The final shape of this area depends on the extent of necrosis and the degree of collapse. All of the findings are correlated with disease progression and the extent of necrosis. This is the active phase, and it can last 12-40 months.

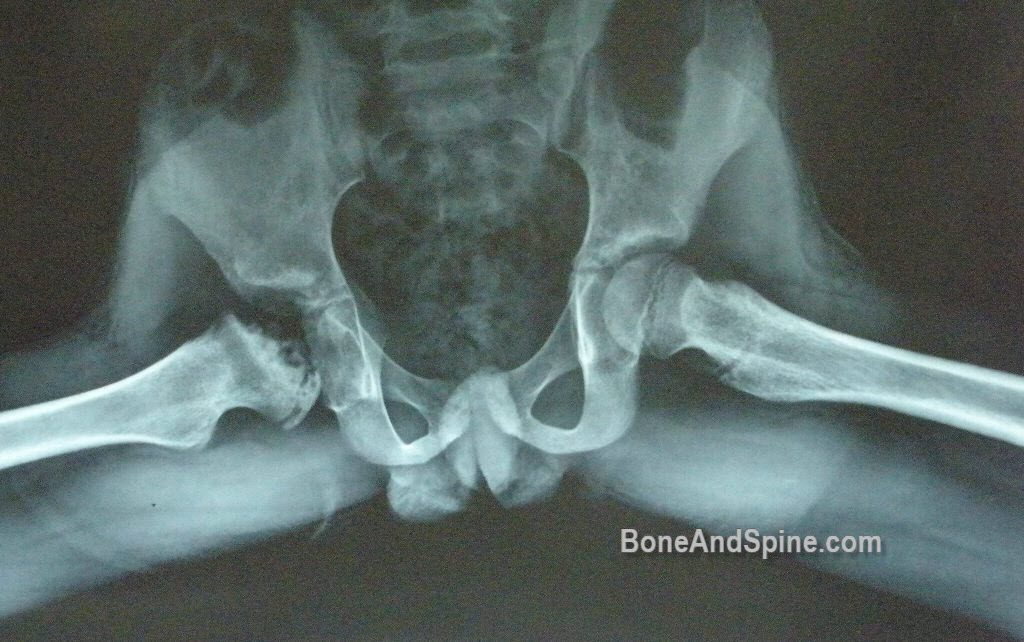

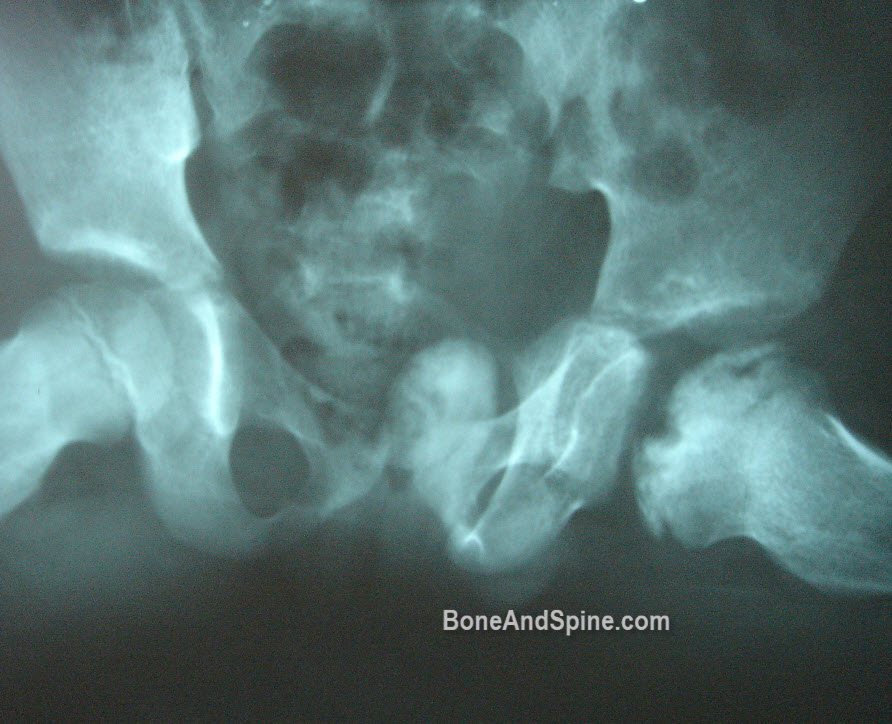

Another x-ray of Perthes disease with advanced features. First AP view

Here is the lateral view

Bone scan

- Can confirm a suspected case

- Decreased uptake can predate changes on radiographs

Contrast-enhanced MRI

- Early diagnosis

- More sensitive

Treatment of Legg Calve Perthes Disease

Nonoperative Treatment

Goals of the treatment are

- Eliminate hip irritability

- Good range of motion in the hip

- Prevent femoral epiphyseal collapse

- Attain a spherical femoral head when the hip heals

Therapy includes

- Minimal weight bearing

- Protection of the joint by containment of the head

- Keep femur abducted and internally rotated

- Braces can be used if needed

- Limits deformity and minimizes loss of sphericity

- Lessen subsequent degenerative changes

- Drugs for pain as needed

- Periodic clinical and radiographic follow-up until completion of the disease process

- Physical therapy (Range of Motion exercises)

Indications for nonoperative treatment are

- < 8 years of age

- Lateral pillar A type disease

About 60% of the cases would not require operative intervention. Good outcomes are achieved by nonoperative treatment in cases of lateral pillar A and Catterall I groups [see classifications].

Operative Treatment

Surgical management typically involves either femoral osteotomy to redirect the involved portion within the acetabulum or innominate osteotomy. The two procedures yield equivalent results, but femoral osteotomy may cause shortening of the limb, leading to a chronic limp.

Femoral and/or pelvic osteotomy

These are considered in children > 8 years of age, especially lateral pillar B and B/C type. Surgery done before femoral head deformity provides best results.

Surgery does not improve outcome in lateral pillar C type disease.

Osteotomies done are

- proximal femoral varus osteotomy

- pelvic osteotomy

- Salter, triple innominate, Dega or Pemberton osteotomy

- Shelf arthroplasty may be added to prevent lateral subluxation and resultant lateral epiphyseal overgrowth

- valgus and shelf osteotomies

- Indications

- Lateral extrusion of the capital femoral epiphysis producing a painful hinge effect on the lateral acetabulum during the abduction

- osteotomies

- Reposition the hinge segment away from the acetabular margin

- Correct shortening

- improve abductor mechanism

- Indications

- Shelf or Chiari osteotomies

- When the femoral head is no longer containable

Complications

Legg Calve Perthes disease is a is a local self-healing disorder and treatment aims to prevent the following:

- Irregular contouring, flattening or mushrooming of the head

- Shortening and broadening of the neck

- Flattening of the vertical wall of the acetabulum

The development of any of these conditions can result in osteoarthritis at an early age.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the severity of involvement, its subsequent healing, and joint space preservation. Overall, the prognosis for recovery and sports participation is very good for most individuals.

Following risk factors may cause worsened prognosis

- Older age of onset

- Extensive epiphyseal involvement

- Reduced range of motion in the hip

- Premature closure of the growth plate

- Female sex

The long-term prognosis is related to the potential for osteoarthritis of the hip as an adult.

Long-term studies show that most patients do well until the fifth or sixth decade of life in which degenerative changes of the hip become present

Approximately half of the patients develop premature osteoarthritis secondary to an aspherical femoral head.

References

- Heesakkers N, van Kempen R, Feith R, Hendriks J, Schreurs W. The long-term prognosis of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease: a historical prospective study with a median follow-up of forty-one years. Int Orthop. 2015 May. 39 (5):859-63.

- Poul J. Diagnosis of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2004 Oct 30. 6(5):604-6.

- Canavese F, Dimeglio A. Perthes’ disease: prognosis in children under six years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Jul. 90(7):940-5.

- Myers GJ, Mathur K, O’Hara J. Valgus osteotomy: a solution for late presentation of hinge abduction in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008 Mar. 28(2):169-72.

- Zarzycka M, Zarzycki D, Kacki W, Jasiewicz B, Ridan T. Long-term results of conservative treatment in Perthes’ disease. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2004 Oct 30. 6(5):595-603.

- Karimi MT, McGarry T. A comparison of the effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of Legg-calve-Perthes disease: a review of the literature. Adv Orthop. 2012. 2012:490806.