Last Updated on November 20, 2019

Patellar instability or Patellofemoral instability is a frequent cause of symptoms of anterior knee pain and episodes of mechanical instability.

It is also called patellar subluxation syndrome.

There is a difference between symptoms of instability and patellar dislocation, though the former may cause the latter to happen.

The term can denote a sign on physical examination or can be a symptom when the patient gets a feeling of the knee giving way.[The patella slips out of the trochlear groove.]

As instability is a subjective symptom, the objective elements included are patellar maltracking, subluxation or dislocation.

Patellar instability occurs due to morphologic abnormalities in the patellofemoral joint where the patella is prone to recurrent lateral dislocation.

It can develop, also, after traumatic dislocation of the patella in which the medial stabilizers are stretched or ruptured, which eventually can result in recurrent dislocations of the patella.

Chronic patellar instability of the patellofemoral joint and recurrent dislocation may lead to progressive cartilage damage and severe arthritis.

Most patients with patellar instability are young and active individuals [second decade].

Redislocation risk is reported to be highest amongst girls aged 10-17 years.

Prevalence is 6-77 per 100,000 population.

Anatomy and Biomechanics of Patellar Instability

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone and is located between the quadriceps and patellar tendon. It serves as a biomechanical lever, magnifying the force exerted by the quadriceps on knee extension.

It also functions to centralize the divergent forces of the quadriceps muscle and thus transmitting the tension around the femur to the patellar tendon.

Patellofemoral joint stability is maintained by static as well as dynamic stabilizers.

Static Stabilizers

[read anatomy of Patella]

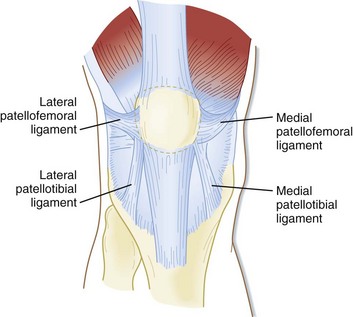

Retinacular Structures

These are medial and lateral retinacular structures. They are most effective within the range of 20° flexion and full extension. During this, the patellofemoral joint is most vulnerable as other stabilizing forces are not active yet.

Medial structures

These include three ligaments

- Patellofemoral ligament

- Patellomeniscal ligament

- Patellotibial ligament

Medial patellofemoral ligament is the most important of all. It is a continuation of the deep retinacular surface of the vastus medialis obliquus. It runs transversely between the proximal half of the medial border of the patella to the femur between the medial epicondyle and the adductor tubercle.

Lateral Structures

The superficial layer consists anteriorly of the fibrous expansion of the vastus lateralis and posteriorly it is formed by superficial oblique retinaculum further posteriorly.

Deep layer Consists of following ligaments

- Epicondylopatellar ligament [also called lateral patellofemoral ligament]

- Deep transverse retinaculum

- Patellotibial band

The epicondylopatellar ligament is indirectly attached to femur via the proximal and distal attachments of the iliotibial band. Thus tightness of iliotibial band would influence the lateral stability force inferred

Trochlear geometry

Patella enters trochlea at 20-30 degrees of flexion, after which the bony anatomy of trochlea offers inherent stability.

Trochlea is concave to accommodate convex patellofemoral joint. [Normal sulcus angle of 138?±?6° on Merchant view].

The lateral femoral trochlea extends further anteriorly than the medial side, providing a buttress to lateral patellar subluxation.

Moreover, the lateral ridge of the trochlea extends further proximally than it does on the medial side, thus engaging the patella in early knee flexion and deflecting it medially. [Thus providing a lateral check.]

Decrease in trochlea depth or trochlear dysplasia is an important risk factor for recurrent patellar dislocation

Patella geometry

Congruity between the patella and the trochlea provides some degree of constraint to the patellofemoral joint. On knee bending, the initial contact area is the distal and lateral patella facet initially and with further flexion, the contact area on the patella articular surface moves more proximally until in deep flexion when medial facet makes contact. The shape of the patella and more importantly the cartilage may impact the stability..

Patella Height

With patella alta, the engagement of patella into the trochlear does not occur in the early phase of knee flexion, thus potentiating instability at the patellofemoral joint.

Limb Alignment

Q angle is an important determinant of limb alignment. It is defined as [8 to 10° and in females, it is 15 ± 5°].

An increase in the “Q” angle results in an increased valgus vector to the patellofemoral joint. Genu valgum, increased femoral anteversion, external tibial torsion and/or a lateralized tibial tuberosity can all ultimately affect patella tracking.

Dynamic Stabilisers

Vastus medius oblique and vastus lateralis muscles are the important dynamic stabilizers.

The vastus medius obliquus overlies and merges with the medial patellofemoral ligaments to provide active and passive stabilization of the patella.

Risk Factors for Patellar Instability

On MRI, the primary contributing findings to patellar instability are trochlear dysplasia (85% of abnormal cases), quadriceps dysplasia/patellar tilt ( 83% of abnormal cases), patella alta (present in 24% of abnormal cases) and tibial tuberosity–trochlear groove distance (increased in 56% of abnormal cases).

The following are the risk factors for patellar instability –

- Trochlear dysplasia – trochlear joint surface is flattened

- Patella alta

- Lateralization of the tibial tuberosity

- Femorotibial malrotation

- Genu recurvatum

- Increased femoral anteversion

- Medial Retinaculum injury

- Ligamentous laxity

- Abnormal muscle tone

- Medial patellofemoral ligament insufficiency

- Increased Q-angle

- Inadequate vastus medialis obliquus

Clinical Features

Patients may complain of anterior knee pain and episodes of mechanical instability. The patient may complain of buckling of the knee under certain circumstances.

The pain is aggravated activities such as stair climbing/getting down, running, hopping and jumping, and changing direction.

Patellar dislocation may take place as a direct traumatic event in some cases.

Another thing that may occur is patellar subluxation. Subluxation or lateral translation will involve the transient lateral movement of the patella.

In general, it is early in knee flexion such that the patient will experience a feeling of pain or instability.

Joint stiffness and creaking or cracking sounds during movement may be reported.

Joint swelling which persists or occurs recurrently may be reported.

A physical examination would vary with the presentation.

In an acute dislocation, deformity and swelling are assessed and the patient is taken for a reduction on an emergency basis.

Palpation of the patella may reveal a palpable defect at the medial patellar margin and tenderness along the course or at the insertion of the medial patellofemoral ligament. Muscle atrophy may be seen in vastus medialis obliquus if there is a disruption of the muscle.

There would be of hypermobility of patella in the lateral and medial directions

In chronic cases, apart from knee inspection and palpation, physical examination includes assessment of

- Lower limb alignment in coronal, sagittal and axial planes

- Any evidence of joint hyper laxity

- Q angle

- Special Tests

Special Tests

Patellar glide test

In this test, the patella is forced to glide by the examiner by pushing it first medially and then laterally. The test is done in 30 ° knee flexion.

The normal movement is less than two quadrants in a medial and lateral direction.

A medial/lateral displacement of the patella greater than or equal to 3 quadrants indicates incompetent lateral/medial restraints.

Less than one quadrant movement indicates tightness of the structures.

Lateral patellar instability is more frequent than medial instability.

Apprehension test

The examiner holds the relaxed knee in 30 ° of flexion and manually subluxes the patella laterally. When the test is positive, the patient complains of pain and anxiety, resisting any further lateral motion of the patella [defensive contraction of muscles]

This may be so positive that the patient pulls the leg back when the therapist approaches the knee with his hand, preventing so any contact, or the patient grabs the therapist’s arm.

The test carries almost 100% sensitivity.

Patellar-gravel test or Clarke Test

The patient is positioned in a supine or sitting position with the involved knee extended. The examiner places the web space of his hand just superior to the patella while applying pressure. The patient is instructed to gently and gradually contract the quadriceps muscle.

Another variation of the test involves pushing down on the patella directly.

A positive sign on this test is a pain in the patellofemoral joint.

J-Sign

This sign checks for lateral patellar tracking and is not very specific for patellar instability. The patient sits with knee bent 45°. Examiner instructs the patient to straighten knee while observing patellar tracking

If the examiner observes patellar deviation laterally [makes the shape of the letter “J”]

It probably shows dysfunction of patellar tracking dysfunction, vastus medialis oblique deficiency or increased Q-angle.

Imaging

Standard x-rays include anteroposterior and lateral views of the knee.

X-rays may reveal osteochondral fractures, osteoarthritis of the tibiofemoral joint and loose bodies.

Lateral view x-rays can tell about patellar height and calculation of different indices.

Trochlear depth can be known from lateral views as well.

Crossing sign is present in trochlear dysplasia. The “crossing sign” represents abnormally elevated floor of the trochlear groove rising above the top of the wall of one of the femoral condyles, assessed on lateral radiographs. The base of the trochlear crosses the line of the lateral femoral condyle.

“Double contour sign” is a double line at the anterior aspect of condyles, and seen if medial condyle is hypoplastic.

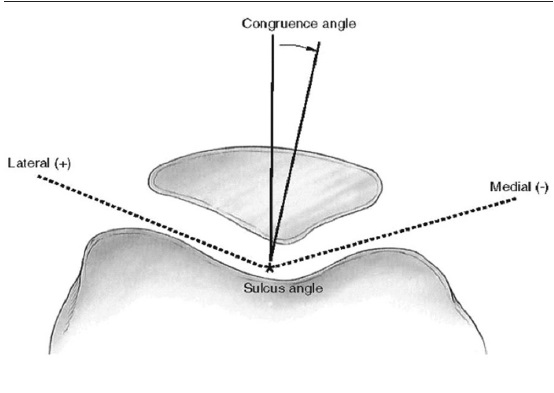

Skyline view can show decreased trochlear depth and large sulcus angle (>144º).

Congruence angle of Merchant

- Bisect the sulcus angle to establish the zero reference line.

- Identify the lowest point on the articular ridge of the patella

- Draw a line from the vertex of sulcus angle to the lowest point on the ridge.

- Angle between this line and the reference line is the angle of congruence

- If an angle is medial to a reference line, it carries a negative value

- If lateral it carries a positive value

- Normal angle is defined as < – 16 deg;

CT

Computed tomography is able to provide a three-dimensional view of the patellofemoral joint.

CT scans are reported to be more accurate and sensitive in detecting abnormal tracking, tilt, and subluxation.

They are also helpful in the assessment of lower limb alignment, femoral anteversion, and lateralization of the tibial tubercle

A tibial tubercle to trochlear groove distance of greater than 20 mm [patellar translation] is virtually always associated with patella instability.

MRI

MRI is considered as the gold standard investigation. It provides reliable images of soft tissue and articular surface.

Measurements similar to those made with CT scans can be easily accomplished.

MRI can be helpful in demonstrating chondral defects, patellar and trochlear dysplasia, patellar tilt, tibial tubercle offset, patellar height, avulsion fragments, and the integrity of the retinacular or patellofemoral ligamentous structures.

Articular cartilage contour can be different from that of the underlying bony contour, therefore MRI a useful adjunct especially when planning surgery.

Associated radiological findings can be in patellar instability are

- knee joint effusion

- Medial patellofemoral ligament tear

- Bone contusion in patella and lateral condyle

- Osteochondral defects in patella

- Edema/hemorrhage of vastus medialis

- Intra-articular loose bodies

- Internal derangement of knee

Chronic patellar instability, if not treated, may lead to severe arthritis and chondromalacia patellae.

Treatment of Patellar instability

Conservative Treatment

For patellar instability, conservative treatment should be attempted first. Surgical intervention should be reserved until conservative measures have failed.

In the acute phase, it includes anti-inflammatory analgesia, ice therapy, elevation and a period of immobilization. The treatment aims at reduction of inflammation and relief of pain.

Bracing and taping have been recommended but more evidence is required.

In acute dislocation of patella, immobilization for a period followed by physical therapy is chosen as treatment. The duration of immobilization may be up to six weeks.

In acute circumstances, indications for surgery include complicated dislocations with associated osteochondral fractures.

The physical therapy includes closed-chain exercises and passive mobilization followed by muscle strengthening exercises.

It is very important in the rehabilitation program to strengthen the quadriceps muscle and VMO.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery may address either bony or soft-tissue components, in a proximal or distal procedure

Lateral release

It was commonly performed in the past but most studies have shown disappointing mid and long-term results. Overzealous or inappropriate lateral release can lead to further medial patellar instability.

Lateral release should only be used as an adjunct to proximal or distal realignment procedures or medial retinacular repair.

Medial repair

Repair, imbrication (reefing) or plication of the medial retinacular structures are designed to strengthen the medial structures. These procedures can be performed in an open, arthroscopic or as an open-arthroscopic technique.

Thermal reefing has been also reported. Usually, the procedure is done in conjunction with a lateral release..

Medial Patellofemoral Reconstruction

MPFL reconstruction offers an appropriate treatment modality in a chronic situation.

This is a relatively newer interest. The construction of medial patellofemoral ligament can be done using grafts have from semitendinosus, gracilis, quadriceps tendon or adductor magnus.

Mesh-type artificial ligament has also been reported.

Bony realignment procedures

Tubercle Realignment Procedures

A common form of malalignment is a large Q angle or increased tibial tubercle to trochlear groove offset. Reducing the Q angle by medialising the tibial tubercle insertion has a role in patellar realignment surgery.

The Elmslie-Trillat procedure

It consists of

- Lateral retinacular release

- Medial capsule reefing

- Medial transposition of the anterior tibial tubercle

This procedure is effective in resolving patellar instability but it is not as successful for patients whose main complaint is anterior knee pain. This may lead to overloading of the medial patellar articular causing patellofemoral arthritis.

Distalization of tibial tubercle

Distalisation in cases of patella alta with instability. Distalisation of the tibial tubercle during the procedure can inherently induce medialisation due to tibial torsion, and thus can result in over medialisation

Fulkerson Procedure

This entails medialisation of the tibial tubercle in order to correct the Q angle with anteriorisation of the tubercle. The anteromedialisation of the tibial tubercle elevates the distal pole of the patella, which in turn reduces contact on the distal patella during early knee flexion, thus potentially alleviating anterior knee pain symptoms and preventing arthritic progression.

Potential disadvantages of this procedure, however, include the more invasive nature of the operation, a larger osteotomy, more reports of tibial fracture, and a prolonged rehabilitation.

Trochleoplasty

In most cases, trochlea dysplasia is mild and well tolerated by patients.

This technique is indicated in severe dysplasia with a trochlear bump of greater than 6 mm, trochlear dome, abnormal patellar tracking and/or failed previous surgery.

The methods for deepening trochleoplasty include lateral facet elevating and sulcus deepening) among others. have been shown to prevent recurrent instability, but may cause ongoing pain due to damage of the articular cartilage, trochlear necrosis, arthrofibrosis and incongruence of the patella.

Patellar osteotomy

With a dysplastic patella, the possibility of conducting a longitudinal patella osteotomy exists. Lateral positioning of the patella can result in increases in patellar pressure. By performing a lateral osteotomy the medial facet can improve the medial contact of the facet in the trochlear groove and has been reported to have a good analgesic effect in the literature

It is rarely performed.

References

- Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability; an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2:19–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01552649

- Conlan T, Garth WPJ, Lemons JE. Evaluation of the medial soft-tissue restraints of the extensor mechanism of the knee. J Bone J Surg Am. 1993;75:682–693.

- Grelsamer RP, Klein JR. The biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:286–298.

- Tecklenburg K, Dejour D, Hoser C, Fink C. Bony and cartilaginous anatomy of the patellofemoral joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:235–240.

- Beaconsfield T, Pintore E, Maffuli N, Petri GJ. Radiological measurements in patellofemoral disorders. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;308:18–28.

- Stanciu C, Labelle HB, Morin B, Fassier F, Marton D. The value of computed tomography for the diagnosis of recurrent patellar subluxation in adolescents. Can J Surg. 1994;37(4):319–323.

- Sillanpaa P, Mattila VM, Visuri T, Maenpaa H, Pihlajamaki H. Ligament reconstruction versus distal realignment for patellar dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(6):1475–1484.

- Arnbjornsson A, Egund N, Rydling O, Stockerup R, Ryd L. The natural history of recurrent dislocation of the patella: long-term results of conservative and operative treatment. J Bone J Surg Br 74(140–2)

- Fulkerson JP, Becker GJ, Meaney JA, Miranda M, Folcik MA. Anteromedial tibial transfer without bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:490–496.

- Bollier M, Fulkerson JP. The role of trochlear dysplasia in patellofemoral instability. J Am Ac Orthop Surg. 2011;19(1):8–16.