Last Updated on July 31, 2019

Rotator cuff tendonitis [also termed as supraspinatus tendonitis] is inflammation of the supraspinatus/rotator cuff tendon and/or the soft tissues around them. Rotator cuff tendonitis is a common cause of shoulder pain in sportspersons and laborers whose profession involves throwing and repetitive overhead motions.

If rotator cuff tendonitis is not diagnosed and treated promptly and correctly, it can progress to rotator cuff degeneration and eventual tear. Adhesive capsulitis, cuff tear arthropathy, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy may also occur.

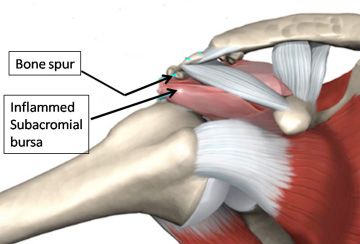

Impingement implies compression of the rotator cuff in the supraspinatus outlet space and is thought to be an important cause of rotator cuff tendonitis.

Relevant Anatomy

The shoulder joint is formed by two bones, namely, humerus, scapula, and clavicle, and there are two joints, one between head of the humerus and glenoid cavity of the scapula and between acromion process of scapula and clavicle.

Shapes of the articular surfaces, glenoid labrum, joint capsule, ligaments, and negative pressure in the joint are the static stabilizers whereas rotator cuff, long head of the biceps tendon, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and serratus anterior are dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder.

The rotator cuff consists of 4 muscles – supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles are responsible for control of shoulder abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation

Anatomy of the acromion is said to be associated with the risk of impingement.

There are four types of acromion

- Inferiorly curved

- Parallel to the humeral head with concave under surface [ most common type]

- Hooked – Anterior portion of the acromion has a hooked shape. This type is associated with an increased incidence of shoulder impingement

- Convex – The undersurface of the acromion is convex near the distal end [compare with type 2]

Cause of Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Rotator cuff tendonitis or supraspinatus tendonitis can occur due to primary impingement [due to increased subacromial loading], or secondary impingement [rotator cuff overload and muscle imbalance].

External causes of Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Primary Impingement

Increased subacromial loading, direct trauma, repetitive injuries and overhead activities [sports and nonsports] are major causes of primary impingement.

Glenoid impingement is said to be present when there is increased tensile stresses on the rotator cuff tendon either from an abnormal motion of the glenohumeral joint or from increased forces on the rotator cuff necessary to stabilize the shoulder.

Secondary Impingement

Rotator cuff overload/soft tissue imbalance, glenohumeral laxity or instability, weak or lax long head of biceps tendon, labral lesions, scapular dyskinesia, posterior capsular tightness, and trapezius paralysis cause secondary impingement.

Repetitive stresses on glenohumeral stabilizers, result in microtrauma and weakening of the ligaments and leading to subclinical glenohumeral instability. Such instability places increased stress on the dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint, including the rotator cuff tendon.

Internal Causes Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Hooked acromion, the presence of an os acromiale, calcific deposits in the subacromial space, osteophytes on the undersurface of the acromion, coracoacromial ligament hypertrophy, subacromial bursal thickening and fibrosis, prominent greater tuberosity, primary tendinopathy, decreased blood supply and calcific tendinopathy also lead to compromise of space and thus impingement.

Impingement is maximum in the forward flexed and internally rotated position as this position brings greater tuberosity of the humerus into the undersurface of the acromion and coracoacromial arch.

Presentation of Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

To begin with, the symptoms are usually mild. The pain could be present at rest and worsened by activity. There may sudden pain with lifting and reaching movements pain triggered by raising or lowering the arm. Sportspersons may report pain when using the shoulder as in throwing or serving a tennis ball.

The pain may also radiate the front of the shoulder.

With the progress of the condition, the pain may occur in the night and there may be a loss of strength and a decrease in range of motion of the affected shoulder. The patient may find activities that require taking the arm behind the back, difficult.

The range of motion should be examined. The patient should be examined for hyperlaxity.

Tests For Impingement

Neer test

The examiner performs maximal passive abduction in the scapular plane, with internal rotation, while scapula is stabilized.

This causes impingement of supraspinatus tendon against anterior inferior acromion.

Hawkins-Kennedy Test

With patient sitting, the elbow is flexed at to 90°, supported by the examiner. The examiner then stabilizes proximal to the elbow with their outside hand and with the other holds just proximal to the patient’s wrist. He then quickly moves the arm into internal rotation Pain and a grimacing facial expression indicate impingement of the supraspinatus tendon, and this is a positive Hawkins-Kennedy impingement sign.

Impingement Test

10 mL of a 1% lidocaine solution into the subacromial space and then repeats the tests for the impingement sign. Reduction of pain constitutes a positive impingement test result.

Drop Arm test

This evaluates for a supraspinatus muscle tear. In this test, the shoulder is abducted 90 degrees, flexed to 30 degrees and point thumbs down. The test is positive if the patient is unable to keep arms elevated after the examiner releases.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qvwYEoeHPaA

Supraspinatus Isolation Test

It is also known as empty can and full can test. The original test described by Jobe and Moynes to test the integrity of the supraspinatus tendon is called empty can test. Full Can Test was later suggested by Kelly as it was less provocative and tested in the same manner.

Empty can and full can represents the position. The patient is tested at 90° elevation in the scapular plane and full internal rotation (empty can) or 45°external rotation (full can).

In these positions, downward pressure exerted by the examiner at patients elbow or wrist. Muscle weakness or pain or both represent a positive test.

Tests for Instability

Sulcus sign

In this test, the examiner grasps the patient’s elbow and applies downward traction. Dimpling of the skin subjacent to the acromion (the sulcus sign) indicates inferior humeral translation. This indicates instability of the shoulder joint.

Anterior Drawer Test

With the patient in sitting position, one hand stabilizes the shoulder by holding coracoid and spine of scapula, and the other hand moves the humeral head anteriorly and posteriorly. Abnormal movement is noted.

The Apprehension and Relocation Test

With patient in supine position, the examiner brings the affected arm into an abducted and externally rotated position. If patient apprehensively guards and does not allow further motion, it indicates a positive anterior shoulder instability.

The test is repeated with shoulder supported anteriorly. The absence of guarding and pain confirms the instability.

Differential Diagnoses Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

- Myofascial Pain

- Bicipital Tendonitis

- Brachial Plexus Injury

- Cervical Disc Injuries

- Infraspinatus Syndrome

- Rotator Cuff Injury

- Cervical Discogenic Pain/ radiculopathy/ cervical disc injuries

- Clavicular Injuries

- Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

- Superior Labrum Lesions

Imaging Studies in Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Xrays are done to rule out glenohumeral/acromioclavicular arthritis and os acromiale.

AP view, internal rotation view of the humerus with a 20° upward and axillary view are most useful to rule out subtle signs of instability and to find an os acromiale.

Stryker notch view also let os acromiale be easily visualized.

Supraspinatus outlet view is used to assess the supraspinatus outlet space and anatomy of the acromion. [if supraspinatus outlet space 7 mm, the patient is more at risk for impingement syndrome.]

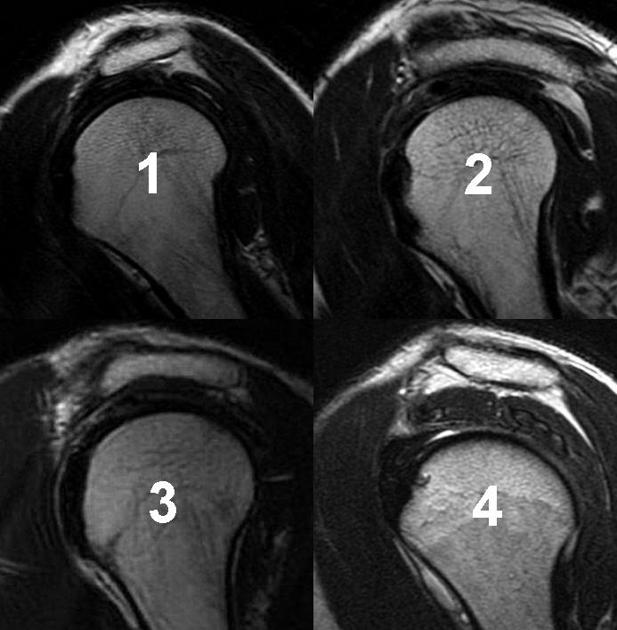

MRI is considered the imaging study of choice which can detect tendon degeneration or partial rotator cuff tears. It can also detect inflammation, swelling, bleeding, and scarring.

Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Reduction of pain and restoration of function are the main goals of the treatment. Treatment is affected by age, general health, and levels of activity.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Initial treatment is almost always nonoperative. The treatment consists of NSAIDs, rest and activity modification in the acute phase and followed by physical therapy.

Physical therapy consists of stretching exercises in the initial period and strengthening exercises after that. Steroid injections along with local anesthetic are used if above therapy does not relieve the pain. The injection is applied to the bursa beneath the acromion.

Surgical Treatment

60-90% of patients improve with nonsurgical treatment over a period of 3-6 months.

If the patient does not benefit and other conditions are absolutely ruled out, the patient is considered for surgery.

The goal of surgery is to create more space for the rotator cuff. For this inflamed part of the bursa is removed and if required part of the acromion is removed [anterior acromioplasty]. The whole procedure is known as a subacromial decompression. These procedures can be performed using either an arthroscopic or open technique.

Professional activities are restricted until full, painless range of motion is restored, the patient is pain-free at rest as well as with activity and there are no signs of impingement.