Last Updated on July 30, 2019

Pelvic fractures and soft tissue injuries break the continuity of pelvic ring.

Most pelvic fractures are stable and occur with a low-energy mechanism of injury. However pelvic fractures can be unstable. These unstable fractures are usually a result of high energy trauma and are associated with injuries to surrounding viscera, vessels and nerves and are commonly associated with injury to other parts like head, chest, abdomen, spine, and extremities.

Pelvic fractures may be associated with a lot of internal or external bleeding. The bleeding may come from exposed fractures, soft-tissue injury, and local veins or less commonly artery.

Low energy and stable fracture of pelvis heal well without much problem. But unstable and displaced pelvic fractures may cause significant deformity, pain, and disability.

Traditionally, pelvic fractures have been treated non-operatively but there is an increased trend to operate the unstable pelvic fractures. This has been made possible by better management of patients with multiple injuries, better implants, a better understanding of injury and deformity pattern.

Operative management allows earlier patient mobilization and prevention of significant pelvic deformities.

Pelvic Fractures – Mechanism of Injury

The low-energy pelvic injury is produced by a fall from a low height such as occurs with tripping. This injury type is often seen in elderly, osteoporotic patients. High-energy injuries are usually caused by vehicular or industrial trauma or by falls from greater heights.

The most common high-energy mechanism of injury is a motor vehicle accident.

A pelvic fracture can occur either due to direct injury or indirect injury. Direct injury mechanism is seen in AP compressions and lateral compression where forces are applied directly to the pelvic ring, indirect injuries are seen in abduction–external rotation and shear.

These forces are discussed below –

Anteroposterior Force Pattern

In this force, the, the pelvis is usually disrupted at the pubic symphysis and springs open, injuring the pelvic floor and anterior sacroiliac ligaments, hinging on the intact posterior ligaments. This force more commonly results in only rotational instability because the posterior ligamentous complex remains intact.

Lateral Compression Force

This is the most common type of pelvic injury. It could be of the following types.

- A force is directed over the anterior half of the iliac wing tends to rotate the hemipelvis inward, with the pivot point being the anterior SI joint or anterior ala crushing the anterior portion of the sacrum, and disruption of the posterior SI ligaments. This injury becomes more unstable as disruption of the posterior osseous or ligamentous.

- A force on the posterior aspect of the pelvis creates compression or impaction of the sacrum as force is parallel to trabeculae of the sacrum. There is a minimal soft tissue disruption because the posterior ligamentous structures relax as the hemipelvis is driven inward. It produces a very stable fracture configuration.

- This force can continue to push the hemipelvis across to the opposite side, producing a lateral compression injury on the side of force application and an external rotation injury on the contralateral side leading to being any combination of ramus fractures or fracture–dislocations through the symphysis. The fractures of the pubic rami are typically horizontal in orientation.

- Finally, a force applied over the greater trochanteric region also produces a lateral compression injury, usually associated with an acetabular fracture.

External Rotation–Abduction Force Patterns

This force is usually applied indirectly through the femoral shafts and hips. It is commonly seen in motorcycle accidents. The leg is caught and externally rotated and abducted, a mechanism that tends to tear the hemipelvis from the sacrum.

Shear Force Pattern

Shear fractures are the result of high-energy forces usually applied perpendicular to the bony trabeculae. These forces quite commonly lead to unstable fractures or dislocations or both. Two situations are possible

- Bone fails earlier than ligaments – if bone strength is less than ligamentous strength, the bone fails first resulting in sacral fractures and vertically oriented rami fractures [compare with the horizontal pattern seen in lateral compression.]

- Ligaments fail first – conversely if the bone strength is relatively greater, ligamentous injuries usually occur and manifest with pubic symphysis and SI joint disruptions.

Classification of Pelvic Injury

Tile classification

- Type A – Rotationally and vertically stable

- A1 – Avulsion fractures

- A2 – Stable iliac wing fractures or minimally displaced pelvic ring fractures

- A3 – Transverse sacral or coccyx fractures

- Type B – Rotationally unstable and vertically stable

- B1 – Open-book injuries

- B2 – Lateral compression injuries

- B3 – Bilateral type B injuries

- Type C – Rotationally unstable and vertically unstable

- C1 – Unilateral injury

- C2 – Bilateral injuries in which one side is a type B injury and the contralateral side is a type C injury

- C3 – Bilateral injury in which both sides are type C injuries

Young and Burgess

This classification is based on the mechanism of injury and types of force acting. The classification has three major components.

Lateral Compression Injury

LC injuries result from the lateral impact of innominate bone as seen before and are further subdivided into three subtypes

Type I

- The most common lateral compression injury

- Commonly observed in the elderly population

- Posteriorly applied force

- Transverse fracture of the anterior ring and a cancellous impaction fracture of the sacrum posteriorly

- Causes sacral impaction

- Low energy and stable

- Minimal problems with resuscitation.

Type II injury

- Often result in posterior fracture dislocation of the sacroiliac joint (crescent fracture)

- Represent a combination of ligamentous disruption of the inferior portion of the sacroiliac joint

- Anteriorly applied force

- Vertical fracture of the posterior ilium that extends from the middle of the sacroiliac joint and exits the iliac crest

- The posterior superior iliac spine remains firmly attached to the sacrum via the superior portion of the posterior ligamentous complex. The remaining anterior fragment is mobile to the internal rotation but remains relatively stable to external rotation and vertical forces.

- Often associated with head and abdominal injury.

Type III injury

- Laterally directed force on one side of the pelvis and is trapped against an immobile object on the contralateral side

- Lateral compression injury pattern on the side of the laterally directed force and an external rotation injury on the contralateral side

- Disruption of the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and anterior SI ligaments

- Usually the result of an isolated direct impact (crush) to the pelvis like run over by a car.

Anteroposterior Compression injury

APC injury results from an anteriorly-directed force applied directly to the pelvis or indirectly via the lower extremities (see the image below). The result is an external rotation force on the innominate bones and an open-book type injury.

Type I

- <2.5 cm of anterior ring diastasis

- Vertical fractures of the pubic rami or disruption of the symphysis.

- No significant posterior injury

- Minimal resuscitation problems

Type II

- High energy injuries

- >2.5 cm of anterior ring diastasis

- Opening of the sacroiliac joints, resulting in rotational instability.

- Significant resuscitation requirements

- Tearing of the anterior SI, sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments

- Posterior SI ligaments remaining intact

- Rotationally unstable and are more likely to be associated with neurovascular injuries, soft tissue complications, and hemorrhage

Type III

- Complete anterior and posterior disruption

- May require resuscitation

- Globally unstable with significant associated injuries.

- Highest rate of neurovascular complications and blood loss

Vertically Unstable

- Unstable fracture patterns

- Significant retroperitoneal hemorrhage and major associated injuries.

- Vertical translation of the hemipelvis

- Fall from a height and landing on an extended limb

- Anteriorly- the pubic symphysis injury or pubic rami fracture

- Posteriorly – sacroiliac joint disruption.

Denis zone of injury classification

Denis classified sacral fractures according to their zone of injury, as follows:

- Zone I injury – The sacral alar region is involved

- Zone II injury – The sacral foramina are involved

- Zone III injury – The central sacral canal is involved, transverse fractures of the sacrum

Zone III is associated with the highest risk of nerve injuries.

Causes of Pelvic Fracture

Low-energy pelvic fractures occur commonly in adolescents and the elderly.

Adolescents typically present with avulsion fractures of the superior or inferior iliac spines or with avulsion fractures of the iliac apophyses or ischial tuberosity resulting from an athletic injury.

Low-energy pelvic fractures in the elderly frequently result from falls while ambulating or insufficiency fractures, typically of the sacrum and anterior pelvic ring.

High-energy pelvic fractures most commonly occur after motor vehicle crashes. Other mechanisms of high-energy pelvic fractures include motorcycle crashes, motor vehicles striking pedestrians, and falls.

High-energy injuries that result in pelvic ring disruption are more likely to be accompanied by severe injuries to the central nervous system, abdomen, and chest. These are often the results of motor vehicle accidents.

Associated injuries with Pelvic Fractures

A pelvic ring injury can be associated with head, chest, abdominal, and retroperitoneal vascular injuries. Significant pelvic hemorrhage may occur in up to 75 percent of patients. Between 60% and 80% of patients have musculoskeletal injuries, 12% have urogenital injuries, and 8% have lumbosacral injuries.

Soft-tissue injuries

Scrotal, labial, flank and inguinal hematomas commonly accompany pelvic ring injuries and are indicative of intrapelvic hemorrhage. Soft-tissue injury can vary from superficial abrasions and lacerations to closed internal degloving injuries, to open wounds. Perineal, rectal and vaginal lacerations are indicative of severe injuries.

Urethral injuries

Urogenital injuries 12 percent of injuries. Blood at the external urethral meatus, perineal and genital swelling and high-riding prostate gland in the male on rectal examination suggest urethral disruption.

Gross hematuria is the most common clinical finding suggesting a bladder injury.

Associated skeletal injuries

Axial and appendicular skeletal injuries are frequently associated with pelvic ring fractures.

Neurovascular injuries

Vascular injuries are usually lacerations of venous structures. Arterial injuries also occur, but much less frequently than venous injuries.

The prevalence of neurologic injury in pelvic fractures is 3.5-13% and usually occur as injuries to the L5 or S1 nerve roots. L4 nerve root injuries also may occur with severe pelvic ring injuries.

Sacral fractures and SI disruptions have a high incidence of S2-S5 sacral nerve injury. Denis zone III injuries have a 56% incidence of neurologic injury. Sacral nerve injuries frequently involve the bowel and bladder and may also cause sexual dysfunction.

Initial Patient Management

In the Field

The patient needs to be evaluated at the injury site by first responders and a high suspicion for pelvic fracture maintained. A pelvic circumferential compression device can be applied for stabilization of suspected pelvic injury. The basic mechanism of significant blunt trauma should prompt consideration of a pelvic fracture. Signs suggesting pelvic fracture may be present [see table 1]

|

Table 1 – Clinical Signs Suggesting Pelvic Fractures |

|

The initial evaluation should include the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) of trauma care. An available history may indicate the mechanism of injury and could help to predict injury pattern.

Address acute life-threatening conditions. If feasible, external pelvic compression with sheet or device can be done to stabilize pelvis and control bleeding. Avoid excessive movement of the pelvis.

IV access should be obtained for fluid replacement and to administer analgesics. The patient should be closely monitored.

The patient is stabilized and transferred to a hospital where a detailed evaluation of his injuries is done and interventions performed as dictated by priority.

In the hospital

Primary treatment of a pelvic fracture is for pain with narcotic analgesics. Administer antibiotics whenever injuries of bowel, vagina, or urinary tract is suspected. Bleeding is the major life-threatening complication of pelvic fractures, avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be avoided for their antiplatelet effects in initial treatment. They may be considered later if inflammation is a concern.

Narcotic analgesics are the treatment of choice in the acute setting. Morphine, fentanyl, and hydorxycodone are frequently used drugs. Drug combinations can be used.

In the emergency department, the advanced trauma life support recommendations for airway stabilization followed by breathing and circulation are followed.

Aggressive fluid resuscitation is critical in the patient who is hemodynamically unstable. Bladder catheterization is required in patients with hypotension to monitor resuscitation. In the case of unstable pelvic injury, it is better to wait for the urethrography result before catheterization.

| Table 2 – Signs of pelvic instability |

|

Management of pelvic fractures in the immediate setting is centered on controlling hemorrhage and patient stabilization, as these fractures bleed a lot.

To control hemorrhage, the techniques aim at decreasing the volume of the pelvis, thereby limiting the amount of blood that can escape into the pelvic cavity.

A simple method to decrease pelvic volume is to wrap a sheet securely around the patient’s pelvis and can be done in the field itself. Pneumatic antishock garments can also be used. External fixators, external pelvic clamps have been advocated to control pelvic volume, with the added benefit of providing bony stability

After initial resuscitation and stabilization, other non life-threatening injuries are evaluated and managed appropriately.

All patients with sacral fractures must undergo vaginal and rectal examinations in the emergency department. Open pelvic fractures can communicate directly with the rectum, vagina, or skin laceration and may carry mortality as high as 50%.

AP radiograph of the pelvis is also done

Management of Hemorrhage

The usual cause of ongoing pelvic bleeding is disruption of the posterior pelvic venous plexus. Rarely, bleeding from a large vessel such as the common, external, or internal iliac may occur. [Arterial injury to large vessels usually is associated with rapid, massive bleeding and loss of distal pulses.]

Stabilization of the pelvic fractures can maintain or decrease retroperitoneal volume and thereby facilitate tamponade of the bleeding vessels.. Before placement of these devices, the pelvic AP radiograph should be assessed.

Most lateral compression injuries do not usually benefit from emergency stabilization techniques. Unstable AP and vertical shear injuries, however, often require immobilization.

Pelvis can be immobilized by

- Prehospital administration of a pelvic circumferential compression device [PCCD].

- Circumferential compressive linen sheet.

- Vacuum body splints

- Skeletal traction

- Pneumatic antishock garment –historical now interest due to simpler, safer alternatives.

- Specialized pelvic clamps or external fixators

Earlier and more effective use of circumferential compression techniques may well lead to fewer indications for acute pelvic external fixation.

A positive test for intra-abdominal blood in a patient who fails to respond to standard resuscitation protocols warrants an exploratory laparotomy. During laparotomy, packing of the presacral area and retropubic space is carried out, if the retroperitoneal hematoma is expanding. In open pelvic fractures, packing of the area plus a circumferential compressive dressing is needed.

If the patient is stabilized, a contrast-enhanced CT should be done. A patient with contrast extravasation has a high likelihood of significant arterial bleeding requiring embolization.

If the patient remains hypotensive despite emergent pelvic stabilization, control of abdominal bleeding, and retroperitoneal packing, then angiography should be performed immediately and embolization should be done.

Extraperitoneal Pelvic Packing

This technique requires external bony pelvic fixation followed by packing of the pelvic retroperitoneal space via an extraperitoneal route to achieve tamponade. It is performed through a midline incision from the pubic symphysis superiorly. Packing is removed at 24 to 48 hours depending on the patient’s stability.

After the patient has been stabilized

- If any indication of an unstable fracture is noted, urethrography [urethral injuries] and a cystogram [for bladder injuries] should be obtained

- If hematuria is present and these investigations do not reveal a, an intravenous pyelogram should be obtained. In female patients, urethrography is rarely helpful and usually omitted.

In open pelvic fractures, the wound on the anterior aspect of the pelvis or over the flank is relatively clean and can be treated like most open fractures. However, wounds that occur in the buttock and groin regions and any wound in the perineal region have of the risk of fecal contamination.

Any wounds that involve the rectum or the perineal or buttock regions must be debrided and an external fixation device applied. Colostomy, if required, should be done.

Occasionally, in a hemodynamically stable patient, external fixators are applied in the acute phase to facilitate care.

Definitive Management

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is preferred for definitive management and has been demonstrated to provide superior results.

Indications for surgery include the following:

- Pubic symphysis gap greater than 2.5 cm

- Sacroiliac joint dislocations

- Displaced sacral fractures

- Crescent fractures

- Posterior or vertical displacement of the hemipelvis (>1 cm)

- Rotationally unstable pelvic ring injuries

- Sacral fractures in patients with unstable pelvic ring injuries that require mobilization

- Displaced sacral fractures with neurologic injury

- Fractures and dislocations through the SI joint

- Unstable extra-articular SI joint fractures

- Displaced fractures of the posterior ring

- Leg length discrepancy of greater than 1 cm. [attributable to pelvic fractures]

- Significant internal rotation abnormality

ORIF is contraindicated in

- Unstable and critically ill patients

- Severe open fractures

- Crushing injuries

- A suprapubic tube in the operative field.

- Morel-Lavalle lesion [shearing of subcutaneous tissue from fascia leading to large hematoma and fat necrosis under degloved skin]

Accident site information, patient history, and radiographic data, patient’s age, occupation, and expectations play a role in planning definitive treatment.

The following can affect the surgical decision

- Prior abdominal or visceral interventions.

- Abdominal wound closed or open

- Osteotomies if any and their locations

- Presence of suprapubic catheter

- Presence of indwelling Foley

- Scrotal or labial hematoma [indicative of the pelvic floor iknjury]

- Leg length discrepancies

- Neuromuscular and vascular status of the lower extremities

- Rotational instability. [Examination under anesthesia if doubtful.]

Imaging and Radiographic Assessment

Imaging should be done after primary stabilization has been done and life-threatening issues tackled as per priority.

[Note – In acute situations, a trauma AP pelvis film can help initiate treatment in the vast majority of cases. Additional images need not be obtained in the acute phase as this may introduce an unnecessary delay in treatment. The initial evaluation also should include chest radiography to evaluate for pulmonary injuries like pneumothorax, contusion, or acute respiratory distress syndrome or free air in the abdomen.

Before definitive treatment decisions are made, a complete radiographic assessment of the pelvis should be done. Complete evaluation of the pelvis requires AP, inlet, and outlet views and CT of the pelvis in high energy injuries ]

Stable fractures are characterized by one or more of the following

- Impacted vertical fractures of the sacrum

- Nondisplaced fractures of the posterior sacroiliac complex

- Subtle fractures of the upper sacrum [indicated by the asymmetry of the sacral arcuate lines.]

Unstable fractures are characterized by

- Cephalad [towards head] displacement of hemipelvis > 0.5 cm

- Sacroiliac diastasis > 0.5 cm.

A fracture of the fifth lumbar transverse process, previously described as a sign of an unstable pelvis, was found in both stable and unstable injuries and is not a reliable sign of pelvic instability.

All trauma patients in whom the spine cannot be clinically cleared must receive a full cervicothoracolumbosacral (CTLS) spine x-rays.

Anteroposterior Radiograph

The AP radiograph provides an overview of the pelvic injury. This radiograph is also obtained as a component of the initial trauma evaluation and highlights most major pelvic disruptions.

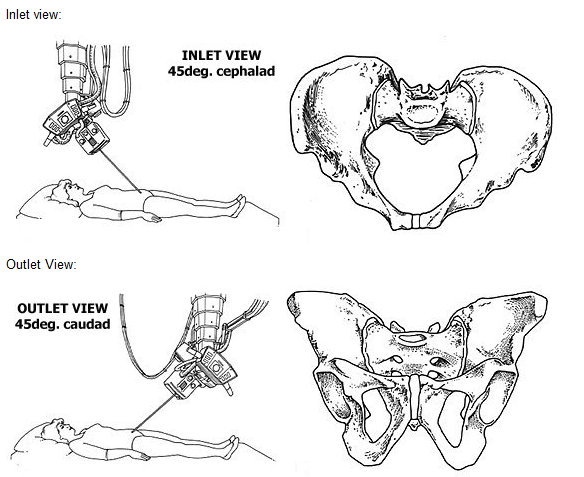

Inlet View

The inlet view is taken with the patient in the supine position. The tube is directed from the head toward the feet at 45°.

On this view, the pelvic brim, the pubic rami, the SI joints, and the ala and body of the sacrum can be seen, as well as the posterior iliac spine. This view is useful for determining the displacement of the SI joint, iliac wing, or fractures through the sacrum. Ischial spine avulsions can also be seen in this view. The axial plane component of rotation (internal or external) may be best appreciated with this view. It highlights AP and mediolateral translations, and internal and external rotatory deformities

Outlet View

The outlet view is taken with the tube directed 45° to the long axis at the foot of the patient. This radiograph highlights superior and inferior translations, abduction and/or adduction, and flexion and/or extension rotational deformities.

Lateral sacral radiograph

It is indicated in injuries sustained from falls and when bilateral sacral fractures are noted on plain radiographs or CT scans A lateral sacral view can help identify transverse sacral fractures and/or kyphosis of the sacrum.

Pelvic Angiograms

An angiogram is indicated in patients with ongoing hemorrhage after adequate intravenous fluid resuscitation and provisional pelvic ring stabilization.

It is also useful in patients who have a pelvic ring or acetabular injuries involving the greater sciatic notch to detect obvious or occult injury to the superior gluteal artery before surgery. Embolization of lacerated arterial vessels may be performed at the same setting,

Retrograde Urethrogram/ Cystogram

Indicated in patients suspected of having urethral tears and bladder injury

Computed Tomography

CT provides better visualization of posterior osseous ligamentous structures of the pelvis and can differentiate crushing injury or a shearing injury of the sacrum. CT is also helpful in defining acetabular injuries and the anatomic abnormalities in preparation for posterior stabilization and treatment of L5-S1 facet joint injuries. Two- and three-dimensional reconstructions of CT scans may provide a more useful evaluation of fracture morphology and of the overall displacement of the fracture.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging is seldom used in acute pelvic fractures.

Ultrasonography

Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is often used as a first-line screen for intra-abdominal bleeding and fluid. It is inexpensive and can quickly provide valuable information, though the test has less sensitivity.

Diagnostic Procedures

Supraumbilical diagnostic peritoneal lavage can be performed to evaluate for an intra-abdominal hemorrhage and a ruptured viscus. It is reported to have a positive predictive value of 98% and a negative predictive value of 97%. If the initial aspirate reveals more than 5 mL of gross blood or obvious enteric contents, an emergency laparotomy is indicated.

Lab Studies

- Complete blood count (CBC) with platelets

- Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

- Liver functions

- Electrolytes

- Blood urea nitrogen

- Creatinine

- Blood group

- Pregnancy test in females

Surgical Procedures

Treatment of associated injuries, particularly injuries to the acetabulum or long bones of the lower extremity, must also be considered when planning operative procedures.

Individual fracture management is touched briefly below

Pubic Symphysis Injury

External fixation or open reduction with internal fixation with plate and screws

Pubic Ramus Fractures

Pubic ramus fractures occur as distraction and compression injuries of the pelvis. Pubic rami fracture surgery is indicated to provide additional pelvic ring stability in association with posterior pelvic ring fixation or in fractures involving the obturator neurovascular canal with accompanying neurologic injury.

Treatment options include external fixation, percutaneous screw fixation, and open reduction and internal fixation.

Iliac Wing Fractures

Simple fracture patterns without associated pelvic ring instability are managed with nonoperative measures.

Severely displaced or comminuted iliac wing fractures, unstable iliac fractures, bowel herniation or incarceration within the fracture, and fractures associated with unstable pelvic ring injuries are indications for open reduction and internal fixation. Preoperative pelvic angiograms are recommended for fractures involving the greater sciatic notch. These fractures are fixed with plates and screws.

Crescent Fractures

Crescent fracture are fractures of the posterior ilium extending from the iliac crest into the greater sciatic notch and are associated with an articular dislocation of the anterior sacroiliac joint.

Crescent fractures are stabilized with lag screws and 3.5-mm reconstruction plates along the iliac wing. Percutaneously placed iliosacral screws also may be used to supplement fixation.

Isolated percutaneous treatment of crescent fractures using iliosacral screw fixation can be used if the posterior iliac fracture fragment is small

Sacroiliac Joint Disruptions

These fractures are stabilized with either 3.5- or 4.5-mm pelvic reconstruction plates placed perpendicular to one another across the SI joint and iliosacral screws

Sacral Fractures

Fractures through the sacrum are probably the most difficult to reduce and stabilize. These are usually are treated by indirect reduction techniques unless a foraminal decompression is required or a closed acceptable reduction cannot be obtained.

Iliosacral screws may be placed in the supine or prone position to stabilize sacral fractures after closed manipulative means.

Open Pelvic Fractures

An open pelvic fracture is a fracture with the site open to the external environment, as well as a fracture site communicating with a vaginal or rectal laceration. Open pelvic fractures are generally associated with significant bony disruption and severe soft tissue damage.

Open pelvic fractures are susceptible to infection and late disability.

A urethrogram and a cystogram reveal the genitourinary involvement. Rectal and vaginal examinations are mandatory in all patients with pelvic fractures. The presence of blood on either examination is an indication for visual inspection of that orifice to rule out an open injury. Evaluation of neurologic status must also be undertaken immediately to determine which structures are not functioning.

A colostomy may be needed. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started immediately.

In fractures with significant contamination involving the perineum or rectum and in situations in which it is impossible to obtain a clean surgical wound, external fixation should be used.

If the wound does not involve the perineum and is not significantly contaminated and if a clean surgical wound can be achieved, the use of primary internal fixation to stabilize the fracture is possible.

If the urethra or bladder is involved and the abdomen has been opened, stabilization of the anterior injury can be done by internal fixation.

After the patient is hemodynamically stable and the pelvis has been stabilized, definitive fracture care can be undertaken.

Complications of Pelvic Fractures

Complications of pelvic fractures are often frequent and severe. In the acute phase, patients are susceptible to the development of adult respiratory distress syndrome, thromboembolic disease, pneumonia, and multiple organ failure.

Infection

Pin tract infection can generally be managed adequately by the appropriate release of the skin about the pins and changing dressings. Loose pins warrant removal.

Postoperative infections after internal fixation require incision and drainage plus debridement. Vacuum dressings are a useful adjunct. Rarely, excision of major portions of the iliac crest is done.

Neural Injury

Permanent nerve damage is a common disability after pelvic fractures. Fractures through or medial to the foramina are associated with a high incidence of neurologic injury, as are transverse fractures of the sacrum with a kyphotic deformity. Reduction and stabilization of these pelvic injuries may improve recovery.

Iatrogenic nerve injury secondary to operative treatment may occur.

Neurologic damage should be managed with an appropriate splint or brace, and surgical intervention should be carried out if indicated. Repair or decompression of the sciatic nerve often is not very successful. Repair of the femoral nerve may be indicated if the nerve has been lacerated.

Morel-Lavalle lesion

It is a significant soft-tissue injury associated with pelvic trauma. The subcutaneous tissue is torn away from the underlying fascia, creating a cavity filled with hematoma and liquefied fat. There is a soft fluctuant area that commonly occurs over the greater trochanter but may also occur in the flank and lumbodorsal region.

Adequate open debridement, sometimes repetitive, is needed.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

DVT occurs in 61% and proximal DVT in about 30% of pelvic fractures. The incidence of symptomatic pulmonary embolism in pelvic trauma is 2-10%.

The risk factors most consistently observed with a trauma population are increasing age, spinal cord injury, fractures of the lower extremity and pelvis, and duration of immobilization.

Routine prophylaxis is recommended with low-dose heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, mechanical devices, and vena cava filters.

Nonunions and Malunion

These occur as a result of inadequate initial treatment of displaced pelvic fractures. Pain is the most common symptom and is usually related to the posterior pelvic injury. The deformity is also common.

A staged reconstruction is often required.

Muscle Ruptures and Hernias

Muscle ruptures and hernias have been reported infrequently with pelvic ring injuries. Bowel perforation, bowel entrapment, and bowel herniation also have been documented with comminuted iliac wing fractures.

Genitourinary Complications

These occur in up to 37% of patients with pelvic fractures. Bladder disruptions and ureteral disruptions, and injury to the ureters and kidneys may occur. Dyspareunia and erectile dysfunction occur in approximately 29% of patients with pelvic ring injuries.

Prognosis

Early stabilization of pelvic ring injuries has demonstrated improved outcomes in patients with pelvic fractures. Stabilization of pelvic fractures immobilizes bleeding cancellous surfaces, thereby.

Injury pattern and reduction of fracture-related displacements have been correlated with outcome results. Injuries involving the sacroiliac joints joint are associated with poorer results when compared with patients with either sacral fractures or iliac wing fractures.

Followings have been associated with poorer outcome

- Posterior pelvic displacement> 5 mm

- Pelvic displacements greater than 1 cm in any plane

- Limb length discrepancy > 2.5 cm

Long-term functional outcome after pelvic ring injury are not well reported and long-term outcome studies are required.

References

- Latenser B.A., Gentilello L.M., Tarver A.A., et al: Improved outcome with early fixation of skeletally unstable pelvic fractures. J Trauma 1991; 31:28-31.

- Brennerman F.D., Katyal D., Boulanger B.R., et al: Long-term outcomes in open pelvic fractures. J Trauma 1997; 42:773-777.

- Matta J.M., Saucedo T.: Internal fixation of pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1989

- Altoona D., Tekdemir I., Ates Y., et al: Anatomy of the anterior sacroiliac joint with reference to lumbosacral nerves. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2000; 376:236-241.

- Brown J.J., Greene F.L., McMillin R.D.: Vascular injuries associated with pelvic fractures. Am Surg 1984; 50:150-154.

- Cotler H.B., LaMont J.G., Hansen S.T.: Immediate spica cast for pelvic fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1988; 2:222-228.

- Cryer H.M., Miller F.B., Evers M., et al: Pelvic fracture classification: Correlation with hemorrhage. J Orthop Trauma 1988; 28:973-980.

- Bottlang M., Krieg J.C., Mohr M., et al: Emergent management of pelvic ring fractures with the use of circumferential compression. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2002; 84(2):43-47.

- Ebraheim N.A., Biyani A., Wong F.: Nonunion of pelvic fractures. J Trauma 1998; 44:102-204.

- Simonian P.T., Routt M.L.C., Harrington R.M., et al: Internal fixation of the unstable anterior pelvic ring: A biomechanical comparison of standard plating techniques and the retrograde medullary superior pubic ramus screw. J Orthop Trauma 1994; 8:476-482.

- Krieg J.C., Mohr M., Ellis T.J., et al: Emergent stabilization of the pelvic ring injuries by controlled circumferential compression: A clinical trial. J Trauma 2005; 59(3):659-664.

- McCoy G.F., Johnstone R.A., Kenwright K.: Biomechanical aspects of pelvic and hip injuries in road traffic accidents. J Orthop Trauma 1989; 3:118-123.

- Nepola J.V., Trenhaile S.W., Miranda M.A., et al: Vertical shear injuries: Is there a relationship between residual displacement and functional outcome. J Trauma 1999; 46:1024-1030.