Last Updated on October 28, 2023

Lumbosacral transitional vertebra refers to a spectrum of are congenital spinal anomalies involving L5 and adjacent vertebrae and varies from complete fusion of L5 with the sacrum, called sacralization to complete separation of S1 from the sacrum and present as L6, called lumbarization.

When the L5 vertebra fuses completely to the sacrum, 4 lumbar vertebrae exist, whereas when S1 separates entirely from the sacrum, 6 lumbar vertebrae exist

Many intermediate incomplete transitions have also been recognized and classified as LSTV.

The prevalence of LSTV in the general population varies from 4.0% -35.9% with a mean of 12.3%.

In unilaterally occurring malformations, the incidence is significantly higher on the left side, a finding which remains unexplained.

The prevalence of LSTV is higher in men. Sacralization is common in males while lumbarization of S1 is more common in women.

A genetic component involving HOX10/HOX11 has been suggested.

The presence of an LSTV is associated with a higher incidence of a concomitant thoracolumbar transitional vertebra and vice versa.

Types of Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebra

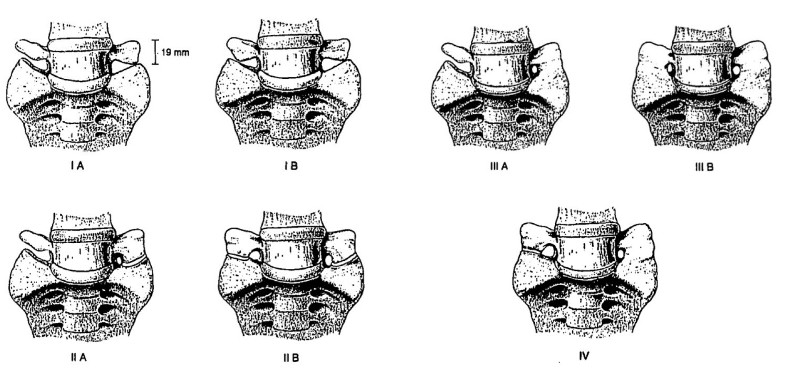

Castellvi Classification

Type I

It includes unilateral (Ia) or bilateral (Ib) dysplastic transverse processes, measuring at least 19 mm in width in craniocaudal dimension.

Type II

Incomplete unilateral (IIa) or bilateral (IIb) lumbarization/sacralization with an enlarged transverse process that has a diarthrodial joint between itself and the sacrum.

Type III

Unilateral (IIIa) or bilateral (IIIb) lumbarization/sacralization with a complete osseous fusion of the transverse process(es) to the sacrum.

Type IV

Unilateral type II transition with a type III on the contralateral side.

Mahato Classification

There is an association between lumbosacral transitional vertebra with morphological alterations of neural arch elements and auricular surfaces is well established.

Mahato classification takes these things into account.

Type I – Dysplastic L5 Transverse Process

Type I A

Unilateral TP less than 19 mm in width

Type I B

Bilateral TPs more than 19 mm in width

Type I A F (i/c) or Type I B F(i/c)

With the presence of ipsilateral/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the L5 enlargement

Type I A F2 or Type I B F2

With the presence of bilateral rudimentary facets

Type II – Accessory articulations

Type II A

Unilateral L5-S1 accessory articulation

Type II B

Bilateral L5-S1 accessory articulations

Type II A F(i/c) or Type I B F(i/c)

With the presence of ipsilateral/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the diarthrosis.

Type II A 2F or Type II B 2F

With the presence of bilateral rudimentary facets

Type III – Sacralisation

Type III A

Unilateral L5-S1 sacralization

Type III B

Unilateral complete sacralization with contralateral L5-S1 pseudoarthrosis

Type III C

Bilateral complete L5-S1 sacralization

Type III A F (i/c) or Type III B F(i/c) or Type IIIC F

With the presence of ipsilateral/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the sacralization

Type III A 2F or Type III B 2F or Type III C 2F

With the presence of bilateral rudimentary facets

Lumbarization

Type IV A

Incomplete/partial lumbarization of S1 as an accessory S1-2 articulation

Type IV B

Unilateral complete separation of S1 from sacral mass

Type IV C

Bilateral S1-2 accessory articulation

Type IV D

Complete sacralization with residual four segment sacrum

Type IV A F(i/c) or Type IV B F(i/c) or Type IV C F or Type IV D F

With the presence of ipsilateral/contralateral rudimentary facet to the side of the diarthrosis

Type IV A 2F or Type IV B 2F or Type IV C 2F or Type IV D 2F

With the presence of bilateral rudimentary facets

Biomechanical and Structural Changes

The presence of a lumbosacral transitional vertebra alters normal spine biomechanics.

The function of the sacrum is to optimize the transfer of the weight of the upper body toward the sacroiliac joint. This function depends on the size and its surface area with the SI joint.

HOX genes regulate segmentation of the vertebral column into individual vertebral segments.

But the formation of transitional states at the lumbosacral junction is thought to be influenced by the functional requirements of load transmission at the sacroiliac junction.

It has been found that in sacrum in the sacralized specimen is smaller in height than the normal sacra if the fused L5 vertebra is excluded from the measurement.

This addition or separation of segments to or from the sacrum depends on the load-bearing capacity of the normal sacrum at a very rudimentary stage of its formation.

Small sacrum with inadequate sacroiliac joint surface area may incorporate L5 to enhance load-bearing capacity, while a sacrum with over competent load bearing capacity may release S1.

Bony abnormalities are associated with the lumbosacral transitional vertebra.

In sacralization, all dimensions, including pedicle height, sagittal and transverse dimensions, and sagittal angulation are reduced, and the downward slope is increased.

The height of the pars interarticularis and the widths of laminae are significantly smaller in the terminal lumbar segment of sacralized specimens, predispose spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis at the lumbosacral junction.

Lumbarization of S1 results in a shorter distance between the facet and sacral promontory, more obtuse pedicles in the sagittal plane and less steep in front.

The orientations and anatomy are important from the surgical viewpoint.

Facet asymmetry is seen in all subtypes.

The disc height below a lumbosacral segment is significantly decreased in types II, III, and IV and may be confused with degeneration or displacement.

The weakness of the iliolumbar ligaments has been noted at the level immediately above transitional vertebrae. It could be responsible for vertebral segment instability and could subsequently lead early disc degeneration.

It is suggested that the articulation or bony union between vertebra and sacrum through the transverse process may represent an adaptive mechanism to compensate for a weak iliolumbar ligament and to preserve stability.

Terminal level of the conus medullaris is significantly higher in the presence of a sacralized L5 and significantly lower in the presence of a lumbardized S1. This might be the reason for the neurological discrepancies observed among neurologic injuries at the thoracolumbar junction.

Due to altered vertebral, neural and possible vascular anatomy, modification of surgical approaches may be necessary.

Pain in the presence of an LSTV may arise from disc herniation or degeneration [also occurs at a younger age than people without LSTV] , facet joint arthrosis, or spinal canal or foraminal stenosis.

LSTV are more likely to be present in patients with clinically significant spinal symptoms and even more so in those operated on for disc herniation of the last mobile disc.

Hypermobility and abnormal torque moments at the level immediately above the transitional vertebra and restricted movement between the L5 and S1 vertebra result in degenerative changes at the level above the anomalous articulation.

Disc protrusion and/or extrusion occurs more often at the level which is suprajacent.

Disc bulge or herniation is exceedingly rare at the interspace below a transitional vertebra.

The incidence of spinal stenosis and spondylolysis is not significantly higher in patients with an LSTV. Though anterior slippage can be more severe when it occurs.

Unilateral LSTV result in asymmetrical biomechanical alterations. The side bearing the additional L5/S1 relationship supports a larger proportion of load, resulting in lateral tipping of the iliac crest. There is convexity of a scoliotic curve towards the side of the articulation.

Asymmetry can cause early degenerative changes and influence disc degeneration.

S1 lumbarization has been implicated in compression neuropathy of the S1 nerve root. Lumbar spinal nerve between the transverse process of the 5th lumbar vertebra and the sacral ala is called Far-Out Syndrome. Extraforaminal entrapment of the spinal nerve leading to radiculopathy.

Neural compression by new bone formation below an LSTV may occur.

Imaging of Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae

X-rays

X-rays in a saggital plane[lateral projection] features suggestive are “squaring” of the transitional vertebral body and reduced height of the transitional disc.

Axial images depict pseudoarthrosis or fusion of the last lumbar vertebra with the sacrum.

The pseudoarticulation between the transverse process and the sacrum may be indicated by sclerotic changes and osteophytes near the false joint.

Standard AP radiographs demonstrate 76%-84% accuracy for lumbosacral transitional vertebra detection.

The 30° angled AP radiograph (Ferguson radiograph) serves as the reference standard method to detect LSTV.

MRI

Exaggerated lumbar lordotic curvature and a lack of sharp angulations at the lumbosacral junction on mid-sagittal MRI suggest lumbosacral transitional vertebra.

An angle formed by a line parallel to the superior surface of the sacrum and a line perpendicular to the axis of the scan table on mid-sagittal T2-weighted MRI is calculated. A value >39.8° suggests LSTV.

The angle formed by a line parallel to the superior endplate of the L3 vertebra and a line parallel to the superior surface of the sacrum, if >35.9° suggests lumbosacral transitional vertebra.

Paraspinal structures in positions outside their frequent location may signify the presence of a transitional vertebra.

Aortic bifurcation, IVC confluence, right renal artery, celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric artery root are located 1-3 levels more caudal than normal in the case of lumbarization, and 1-3 levels more cephalic than normal in the case of sacralization.

But it must be kept in mind that nonspinal landmarks have a variable location and also changes with age.

Correct Numbering of the vertebrae

A lumbosacral transitional vertebra can make correct numbering of lumbar and sacral vertebra difficult on imaged

It is important to ensure a correct number of the vertebra to avoid intervention or surgery at the incorrect level.

On x-rays, by convention, on a sagittal radiograph, the last vertebra with a rectangular shape is generally considered to be L5, and then the vertebral bodies are numbered from the bottom to the top.

In the presence of an LSTV the rectangular shaped last vertebra can be L4 or L6.

This is confirmed by counting from above, T12 downwards. The vertebra with the last rib is deemed as T12 [ But that can be fallacious as many persons have last rib absent]

In such cases/doubt, whole spine images including cervical spine can be used for confirmation, starting from C2 downward.

On MRI, whole spine sagittal T2W images play an essential role in accurate vertebral numbering. Numbering is done caudally from C2 on whole-spine MR images.

In a child, sagittal images of the sacrum and coccygeal bone on T2 weighted can help. The counting is done up from S5 and S1 is determined correctly.

Determination of S1 enables detection of the L5 and, in turn, all other vertebrae.

Clinical Significance of LSTV

Low back pain in the presence of an LSTV was originally noted by Mario Bertolotti in 1917 and termed Bertolotti’s Syndrome.

The potential association between LSTV and low back pain has been debated.

Some authors suggest that lumbosacral transitional segments are quite common and may not be seen with higher prevalence in patients reporting low back pain.

A third opinion suggests that low back pain complaints might be worse, but not more frequent when a lumbosacral transitional vertebra is present.

A diagnosis of Bertolotti’s syndrome should be cautiously considered with appropriate patient history, imaging studies, and diagnostic injections.

References

- Hughes RJ, Saifuddin A. Imaging of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae. Clinical radiology. 2004;59(11):984–91.

- Mahato NK. Redefining lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) classification: integrating the full spectrum of morphological alterations in a biomechanical continuum. Medical hypotheses. 2013;81(1):76–81.

- Konin GP, Walz DM. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: classification, imaging findings, and clinical relevance. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2010;31(10):1778–86.

- Luoma K, Vehmas T, Raininko R, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra: relation to disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine. 2004;29(2):200–5

- Kim YH, Lee PB, Lee CJ, Lee SC, Kim YC, Huh J. Dermatome variation of lumbosacral nerve roots in patients with transitional lumbosacral vertebrae. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2008;106(4):1279–83. table of contents.

- Hughes RJ, Saifuddin A. Numbering of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae on MRI: role of the iliolumbar ligaments. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2006;187(1): W59–65.