Last Updated on October 28, 2023

Chronic ankle instability has is seen in about 20% of people who suffer from acute ankle sprains. It often causes recurrent sprains.

About 80% of acute ankle sprains reach full recovery with initial non-operative management, rest develop chronic symptoms resulting in chronic ankle instability.

[Please go through Acute ankle sprains to get a better perspective of this article ]

In few patients, there may be predisposing factors which may cause or maintain chronic ankle instability like the presence of hindfoot varus and a plantarflexed first metatarsal head. These factors produce early operative failure if not corrected at the time of surgery.

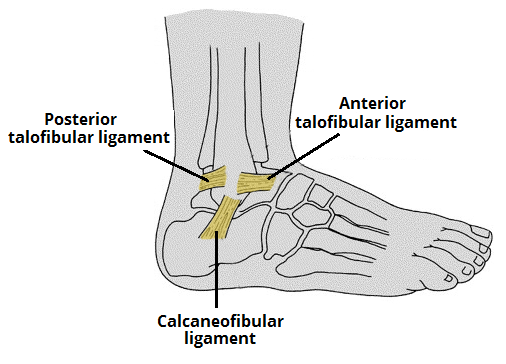

Relevant anatomy

Main ligaments injured in the ankle sprain are lateral ligaments which are anterior tibiofibular and calcaneofibular ligament.

[Read Anatomy of ankle joint ]

[Read more on ligaments involved in ankle sprains]

Causes of Chronic Ankle Instability

The exact etiology of recurrent ankle sprains is unknown

Following factors are thought to contribute

- Lengthening of ligaments due to intervening scar tissue healing in a lengthened position

- Scar tissue filling in the gap between the torn, separated ends.

- The inherent weakness of the scar.

- Persistent peroneal weakness.

- Unrecognized disruption of the distal tibiofibular ligament

- Loss of proprioception in the foot

- Disrupted mechanoreceptors and their afferent nerve fibers

- Dysfunction of the peroneal nerve

- Impingement of the capsular scar tissue in the talofibular joint

- Hereditary hypermobility of joints

Types of Chronic Ankle Instability

Mechanical instability clinically

Mechanical instability is characterized by abnormal ankle mobility, assessed using manual stress application by the anterior drawer and the talar tilt tests.

Functional instability

It is the subjective feeling rather than objective finding. The patient feels the ankle giving way during either physical activity or during common activities of daily living.

Just to differentiate, functional instability movement is the one which is independent of voluntary control, even if the physiological range of motion is not always exceeded.

Clinical Presentation

The main complaint usually is intermittent giving out of the ankle, mostly with physical activity but in quite a number of cases in daily living too.

There would be a past history of acute ankle sprains, often more than one.

The patient is often apprehensive of uneven surfaces where the walking is difficult. Even a mild exacerbation can lead to short-term dysfunction.

There is no pain or dysfunction between episodes.

In some cases, there could be hindfoot varus visible on examination [its one of the factors for recurrent sprains]. Otherwise, the ankle would be normal on examination.

The patient should be examined for general ligamentous laxity. The hindfoot motion should be recorded and peroneal muscle strength should be tested.

Provocative tests like anterior drawer or talar tilt may reveal instability in mechanical stability cases.

Provocative tests are described in Ankle Sprains article.

Abnormal proprioreception may be revealed by modified Romberg test.

Differential Diagnoses

Consider other common causes of pain that occurs/persists after the ankle sprain. There could be missed injuries to

- Anterior process of the calcaneus

- Lateral or posterior process of the talus

- The base of the 5th metatarsal

- Osteochondral lesion

- Injuries to the peroneal tendons

- Injury to the syndesmosis

Imaging

X-rays

AP, lateral and mortise views are useful to rule out bony injury or degenerative changes. Stress x-rays can be useful to find talar tilt and anterior talar translation.

MRI

MRI is more useful than that in the acute setting.

Ligament injury is seen on MRI as swelling, discontinuity of fibers or a wavy ligament etc.

Moreover, MRI is quite helpful in revealing other causes of ankle pain if any. [see the list in arthroscopy]

Arthroscopy

The exact role of arthroscopy is not defined but it can be used to look for other causes that can contribute to pain and dysfunction. These include

- Osteochondral (OCD) lesions of the talus

- Impingement

- Loose bodies

- Painful ossicles

- Adhesions

- Chondromalacia

Treatment of Chronic Ankle Instability

Non-operative Treatment

This consists of functional rehabilitation by strengthening exercises, exercise for proprioception and balancing exercises.

The treatment is continued for 2-3 months. The likelihood of success is decreased with mechanical instability, peroneal weakness, or proprioceptive deficits.

Six weeks of aggressive physical therapy is recommended.

Orthotics can be useful during the rehabilitation process. Bracing may also provide additional support for the chronically unstable ankle.

Operative Treatment

The patients who do not benefit from non-operative treatment should be considered for surgery.

The goal of surgery is to restore the native anatomy of the injured ligaments,[ length, direction, tightness] in order to restore the correct kinematics [anatomic reconstruction] or substitute the injured ligaments [tenodesis].

Some amount of joint stiffness may occur with all the procedures.

Indication for surgical treatment are

- persistent symptomatic mechanical instability

- Failed functional rehabilitation.

Contraindications to surgery are

- Pain without instability

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Peripheral neuropathy

- inability to comply with a postoperative regimen.

Over 80 surgical procedures have been described for chronic lateral ankle instability

Surgical Procedures divided into three categories

- Anatomic repair

- Nonanatomic, or check-rein reconstruction

- Anatomic reconstruction with graft

There are a number of procedures described in each category. Only the commonly done or representative procedures are mentioned.

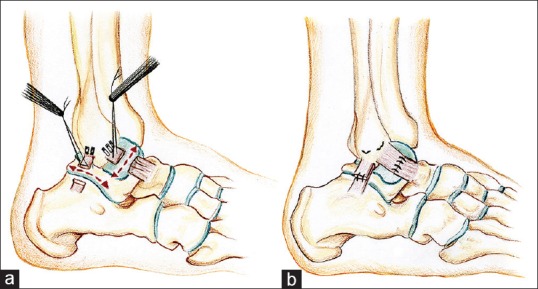

Anatomic Repair

Modified Brostrom procedure includes repair of bone tunnel repair of the anterior tibiofibular ligament and calcaneofibular ligament. Most of the patients [85%] achieve good outcomes.

Increased failure rates are reported in persons with long-standing instability, poor tissue quality, history of the previous repair, generalized ligamentous laxity, and cavovarus foot deformity.

Nonanatomic reconstructions, or check-rein procedures

Modified Watson-Jones routes the peroneal brevis tendon obliquely through the distal fibula in an anterior-distal to posterior-proximal fashion

Chrisman-Snook reconstruction[modification of Elmslie procedure] splits the peroneus brevis tendon and transferred through the fibula and into the calcaneus, thus providing a more anatomic reconstruction

Nonanatomic reconstructions yield mixed results. Issues observed in long-term follow-up are subjective instability, nonphysiologic kinematics, and diminishing clinical outcome scores.

Anatomic Reconstruction

Anatomic reconstruction can be achieved using free autograft or allograft tendon.

The indications are poor tissue quality or revision surgery. The use of free autograft or allograft spares peroneal function or strength.

For reconstruction, the graft is placed into the anatomic origins and insertions of the anterior tibiofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments.

The autograft can be obtained from the gracilis, semitendinosus, fascia lata, palmaris, plantaris, and patella tendons.

The use of allograft, though save from donor-site morbidity, but there is a risk of disease transmission.

Anatomic reconstructions are excellent procedures for high demand ankles with chronic instability.

Postoperative Protocol

The splint is removed at 2 weeks postoperatively and is switched to a removable ankle brace in order to begin gentle range of motion exercises.

Passive inversion stretching is avoided for 6 weeks.

Physical therapy is then started and includes

- Active and passive range of motion

- Gait training

- Strengthening of ankle muscles

- Proprioceptive training

A return to full activity can be expected at 3 to 6 months.

Complications

- Wound complications occur

- Paresthesias

- Neuroma formation

- Late recurrent instability due to chronic attritional injuries.

Recurrence

Acute recurrence is often due to acute reinjury. Late recurrence is due to attritional injuries.

Risk factors for failure and recurrent instability after the operative procedure are

- Ligamentous laxity

- Longstanding instability

- High functional demand

- Cavovarus foot.

Patients with ankle instability and hindfoot varus deformity should be treated with a concurrent calcaneal osteotomy with lateral ankle ligament reconstruction.

Proprioceptive-based therapy is often a preferable option to revision surgery.

References

- Van Dijk CN, Verhagen RA, Tol JL. Arthroscopy for problems after ankle fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):280–284.

- Chan KW, Ding BC, Mroczek KJ. Acute and chronic lateral ankle instability in the athlete. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(1):17–26.

- Caprio A, Oliva F, Treia F, Maffulli N. Reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligaments with allograft in patients with chronic ankle instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):597–605.

- Colville MR. Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:368–377.