Last Updated on November 22, 2023

Segmental instability of lumbar spine is one of the important causes of back pain.

When the forces within physiological limits are applied to the spine, the movements occur within the specific physiological range, with small person-to-person variations.

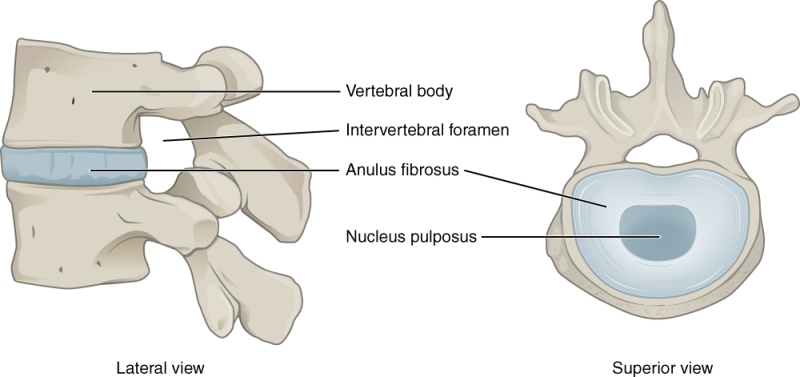

During spinal movements, the adjacent vertebrae maintain their relationship with each other due to the configuration, orientation and integrity facet joints, ligaments and intervertebral discs.

Segmental instability means greater than normal range of motion. The condition often develops when a particular disc or facet joint degenerates to an extent that it no longer supports the weight of the body through that segment.

A spinal segment or motion segment is composed of two vertebrae attached together by ligaments, with a soft disc separating them. The facet joints fit between the two vertebrae, allowing for movement, and the foramen between the vertebrae allows space for the nerve roots to travel freely from your spinal cord to the rest of your body.

Segmental instability can lead to localized pain and difficulties. The excess movement of the vertebrae can cause pinching or irritation of nerve roots, cause inflammation of facet joints and muscle spasms [the paraspinal muscles in your back try to stop the spinal segment from abnormal movement].

Pathophysiology of Segmental Instability

Normally, the spine is stabilized by

- Structural integrity

- Vertebrae, facet joints, intervertebral discs, and ligaments

- the muscles and tendons along with controlling nerves

A problem in any one of the systems [a fractured vertebra, a herniated disc, a muscle strain or tendon sprain, or a pinched nerve], puts added stress.

For example, degeneration of the disc could lead to arthritis of facet joints, osteophytes and eventually worsening segmental instability.

The various stages of development of segmental instability are

- Asymptomatic Hypermobility

- Symptomatic Hypermobility [following a triggering event]

- Occult Instability

- Clinical instability (Usually non-reversible)

Progression of Segmental Instability

Stage of dysfunction

Hypermobile angulation of the functional spinal unit

Stage of instability

Disc and facet joint degeneration set in resulting in excessive translation beginning after the loss of disc height which is the first change in this stage that sets off the cascade. As the degenerative process progresses, more and more translation occurs.

Stage of Restabilization

Severe loss of disc height and osteophyte formation result in destabilization of the unit and the translation will decrease. If restabilization does not occur, the pain will increase – necessitating surgery.

Hypermobility and Clinical Instability

If, while still under the influence of normal physiological loads, the accepted physiological mobility limits are exceeded, a state of hypermobility exists.

This should not be considered as a pathological motion state but rather an extended mobility range.

In many people, this state of hypermobility is not associated with symptoms and signs and is well under normal muscular and ligamentous control. It can occur as a part of inherited generalized skeletal hypermobility, athletic training, yoga practices, professional dancing etc.

With the passage of time, in some people, symptoms like mild pain and stiffness may arise.

The state of clinical instability essentially spells out a soft tissue and sometimes even bony incompetence in maintaining the integrity of the motion segment.

White And Panjabi defined Clinical instability as “the loss of the ability of the spine under physiological loads to maintain relationships between vertebrae in such a way that there is neither damage nor subsequent irritation to the spinal cord or nerve roots, in addition, there is no development of incapacitating deformity or pain due to structural changes.”

The state of Clinical Instability is symptomatic and associated with repeated or continuous pain.

If diagnosed early while in the stage of hypermobility or symptomatic hypermobility, it is possible to avoid progressing into the clinical instability stage. Therefore, diagnosing lumbar instability early is important.

Determinants of Clinical Instability

Many studies have described the association between lumbar degenerative disc disease and segmental instability

Followings are generally considered indicators of instability in the lumbar spine

- Recurrent, acute episodes of low back pain produced by mechanical stresses

- Neurologic deficit related to spinal stenosis

- Confirmatory imaging studies

- Anterior translation greater than 3 mm

- Sagittal rotation greater than 10°

- Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis

- Translational motion greater than 3 mm in the sagittal plane to represent radiographic segmental instability.

A spinal motion segment can undergo two kinds of motion – translatory and rotatory.

The currently accepted thresholds for diagnosing instability for lumbar spine

- Translation

- 4 mm of sagittal plane translation anteriorly

- 2 mm sagittal plane translation posteriorly for translational instability

- Rotational instability

- >15° at L1-L4

- >20° at L4-L5

- >25° at L5-S1

- Angulation > 9 degrees in the sagittal plane

Types of Segmental Instability

Developmental

Hypoplasia of facets

Hypoplasia leads to a small area of contact and, the area is incapable of supporting the superincumbent weight. The L5 pars is predisposed to stress fracture, because of the fulcrum. The increased length of the lever arm exerts greater stress on the pars.

The pars interarticularis gradually elongates and spondylolisthesis results secondary to repeated micro-fractures in the pars interarticularis.

A severe tightness of the hamstrings is likely to result.

Secondary changes like alteration in the shape of the body of L5 may occur.

Severe congenital anomalies of the spine like hypoplasia and mal-development of superior facets of S1 often permit higher degrees of spondylolisthesis and spondyloptosis to occur.

Tropism

Tropism essentially indicates asymmetry of the facets in all the three planes. One of the facets is moon shaped and acts as a fulcrum for rotation. The other facet is flat, straight and is generally sagittally oriented. The facets on this side go through translator/ movement on shear loading. This produces rotation of the segment.

Degenerative

The superior facets of lower lumbar vertebrae are moon shaped with lateral sagittally and anterior coronally oriented portions. With constant dynamic high loads degenerative changes and attrition are common.

During these attritional degenerative changes remodeling of the articular processes occur. Because of this, the bone of the articular processes has a peculiar granular appearance. As the slip progresses, the articular processes on radiographs change direction and become more horizontal.

Primary Instabilities

- Axial rotational instability.

- Translational instability. Prolisthesis/ retrolisthesis

- Progressing degenerative scoliosis.

- Disc disruption syndrome.

Secondary Instabilities(latrogenic)

- Post-disc excision.

- Post-decompressive laminectomy

- Accentuation of pre-existent deformity

- New deformity

- Post-spinal fusion

- Above or below a spinal fusion

- Spinal fusion increases the shear stresses in the next adjacent mobile functional spinal unit

Pathological

- Post Infective

- Neurological

- Neoplastic

Traumatic

- After fracture dislocations

- Facet injuries

- Chronic manipulations

Clinical Presentation

Low back pain is a common symptom reported by up to 30% of patients with segmental instability.

It may present as recurrent acute episodes or chronic pain. The pain may occur on suddenly and in response to a movement. The back may feel weak or may lock on movement.

On examination, one may note muscle spasm and there may be palpable step-off. The painful arc of movement may be seen by asking the patient to flex the trunk. The patient may feel symptoms during a particular point in flexion or on return to the erect position.

Following maneuvers can help to reach at the diagnosis.

Gower Sign

The patient is asked to flex the spine. During the return from flexed to erect by pushing on the thighs or another surface with the hands [ thigh climbing].

Instability catch

Any sudden acceleration or deceleration of trunk movement or movement occurring outside the primary plane of motion. For example lateral bending or rotation during trunk flexion.

Reversal of lumbopelvic rhythm

The patient is asked to flex the spine. On attempting to return from the flexed position, the patient bends the knees and shifts the pelvis anteriorly before returning to the erect position.

Posterior shear test

Prone instability test

The patient lies prone on the examining table and legs over the edge and feet resting on the floor. While the patient rests in this position with the trunk muscles relaxed, the examiner applies posterior to anterior pressure to an individual spinous process of the lumbar spine. Any provocation of pain is reported. Then the patient lifts the legs off the floor (the patient may hold table to maintain position) and posterior to anterior compression is applied again to the lumbar spine while the trunk musculature is contracted.

The test is considered positive if the pain is present in the resting position but subsides in the second position, suggesting lumbo-pelvic instability. The muscle activation is capable of stabilizing the spinal segment.

H and I Tests

Quadrant test

Imaging

X-ray

X-rays are the most widely used method to diagnose instability. On x-rays, the instability is indicated by

- Vacuum phenomenon-gas in the disc space

- One of the earliest signs of segmental instability

- End plate sclerosis

- Traction osteophytes–osteophytes

- 2–3 mm away from the end plate border

- High specificity (98.1%)

- Claw osteophytes at a later stage

- Decrease in disc space height

- Predictive of anterior and posterior translatory instability

- Facetal osteoarthritis

- Predictor for anterior and posterior translatory instability.

- Spondylolisthesis

Special views

Flexion-extension views and lateral rotation views

[Traction-compression views and lateral bending views have been demonstrated to be of no value in diagnosing instability]

For flexion-extension views, the spine of the patient is flexed and extended extensively and an x-ray is taken in both extremes.

Sagittal translatory instability is diagnosed when the translation is > 4 mm or 15% of vertebral body width. The criterion for diagnosing sagittal angular instability is when the sagittal angulation is more than 10°.

Rotary instability is manifested by a double contour of the posterior border of the concerned vertebra. A constant double contour of the posterior borders of all the vertebrae is, however, a consequence of oblique projection and is not due to instability.

MRI

MRI is able to reveal details on tissues. MRI has suggested lumbar segmental instability to have a positive association with annular tears.

Treatment of Segmental Instability or Spinal Instability

Many instabilities are known to stabilize themselves spontaneously, though some of them in malaligned positions. Many of them in spite of the looseness of segments and the painful soft tissue incompetence do not show any further progression of the hypermobility.

A large number of spinal instability patients can be satisfactorily treated by appropriate conservative therapy.

The basic principles in the non-surgical management of spinal instability are as follows :

- Avoiding specific postures

- Making postural readjustments

- Developing and maintaining a ‘good muscular corset’ around the spine.

- Narrowing down the range of movements during activities of daily life.

- Lumbar orthotic bracing.

- Care of other pain-producing trigger points

In the acute phase of low-back pain, the exercise should start within a day or two to help realign the stressed spinal area

Neuromuscular training must then progress through the full range of motion to allow strength and control toward the end of the range where the injury occurs.

Surgery

Surgical management is recommended for patients with severe symptoms restricting activities of daily living or those with radiological evidence of instability who are not responding to a trial of conservative treatment for two months.

The current treatment for symptomatic instability in cases of spondylolisthesis, degenerative disc disease and lumbar canal stenosis is decompression, posterolateral fusion and instrumentation.

References

- Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis.J Spinal Disord 1992;5: 390–6

- Pitkanen M, Manninen H. Sidebending versus flexion-extension radiographs in lumbar spinal instability.Clin Radiol 1994;49: 109–14

- Schinnerer KA, Katz LD, Grauer JN. MR findings of exaggerated fluid in facet joints predicts instability.J Spinal Disord Tech 2008;21: 468–72

- Hasegewa K, Kitahara K, Hara T, Takano K, Shimoda H. Biomechanical evaluation of segmental instability in degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis.Eur Spine J 2009;18: 465–70

- Cook C, Brismee JM, Sizer PSJr. Subjective and objective descriptors of clinical lumbar spine instability: a Delphi study.Man Ther 2006;11: 11–21

- Stanton T, Kawchuk G. The effect of abdominal stabilization contractions on posteroanterior spinal stiffness.Spine 2008;33: 694–701

- Abbott JH, McCane B, Herbison P, Moginie G, Chapple C, Hogarty T. Lumbar segmental instability: a criterion-related validity study of manual therapy assessment.BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6: 56. Gertzbein SD, Seligman J, Holtby R, et al. Centrode characteristics of the lumbar spine as a function of segmental instability.Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;208: 48–51