Last Updated on November 22, 2023

Acromioclavicular joint injuries are also known as shoulder separations, acromioclavicular joint separation or acromioclavicular joint dislocation and occur as a result of downward force on the acromion.

Acromioclavicular joint injuries occur most commonly in sporting activities. These are most commonly seen in young adults although an increasing trend is noted in children due to increased participation.

Acromioclavicular joint injuries are seen especially in competitive athletes[ rugby or hockey players] and occur most frequently in the second decade of life. Males are more commonly affected than females.

Anatomy of Acromioclavicular Joint

The acromioclavicular joint is part of the shoulder girdle and is diarthrodial joint between the acromion process and lateral end of the clavicle. A meniscus, complete or incomplete is present in the joint.

The normal width of the acromioclavicular joint is 1-3 mm. It reduces with age and reduces to < 0.5 mm or less in people older than 60 years due to a reduction in size of the disc.

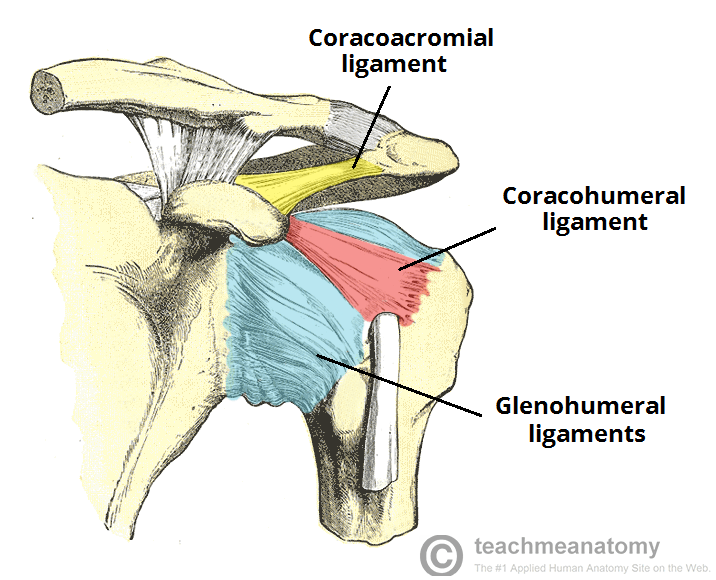

The acromioclavicular joint has a thin capsule stabilized by ligaments and by attachment of the fibers of the deltoid and trapezius muscles.

The horizontal, anteroposterior stability is provided by the acromioclavicular ligaments.

Vertical stability is provided by Coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid) ligaments.

Coracoclavicular ligaments are medial to the joint and extend from the inferior surface of the clavicle to the base of the coracoid process of the scapula.

The deltoid and trapezius muscles are also important in providing dynamic stabilization.

Acromioclavicular ligament and coracoclavicular ligament are the primary static stabilizers of the acromioclavicular joint.

- Anterior and posterior acromioclavicular ligaments – stability in the anteroposterior plane

- Trapezoid and conoid ligaments [parts of coracoclavicular ligaments] – restrain compression and superior-inferior translation,

The deltoid and trapezius muscles provide dynamic stabilization.

[Read detailed anatomy of shoulder joint]

The superior shoulder suspensory complex is a bony and soft-tissue ring composed of

- Glenoid process

- Coracoid process

- Coracoclavicular ligament

- Distal clavicle

- Acromioclavicular joint

- Acromial process

This complex maintains normal scapula relation with an axial skeleton.

An injury to two structures is called double disruption and three structures is called triple disruption.

All acromioclavicular injuries from stage III onwards are double disruptions.

Mechanism of Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

The most common mechanism of injury is a fall directly onto the shoulder.

A direct force applied to the superior aspect of the acromion, usually from a fall with the arm in an adducted position drives the acromion inferiorly.

The acromioclavicular joint is stabilized by a combination of muscular and ligamentous forces. As the joint is transversely oriented, downward forces may cause disruption of the stabilizing structures [acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments].

This same mechanism of injury can result in sternoclavicular dislocations, fractures of the clavicle or acromion.

Mostly these injuries occur in sports but are also common in motor vehicle accidents.

Less commonly, an indirect force may be transmitted up the arm as a result of a fall on an outstretched hand

Classification of Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries [Rockwood]

The degree of damage to the acromioclavicular ligaments and coracoclavicular ligament with resultant displacement of the clavicle relative to the acromion is the primary criterion for the classification of AC separations.

Type I

- Acromioclavicular ligament: mild sprain

- Coracoclavicular ligament: intact

- Joint capsule: intact

- Deltoid muscle: intact

- Trapezius muscle: intact

The radiographs are normal, except for mild soft tissue swelling when compared with the uninjured shoulder [No widening, no separation, No elevation of the clavicle with respect to the acromion and no deformity.

Type II

- Acromioclavicular ligament: ruptured

- Coracclavicular ligament: sprain but intact

- Joint capsule: ruptured

- Deltoid muscle: minimally detached

- Trapezius muscle: minimally detached

The lateral end of the clavicle may be slightly elevated but not above the superior border of the acromion. The acromioclavicular joint may appear to be widened [due to medial rotation of the scapula and posterior displacement of the clavicle by the pull of the trapezius muscle].

Type III

- Acromioclavicular ligament: ruptured

- Coracoclavicular ligament: ruptured

- Joint capsule: ruptured

- Deltoid muscle: detached

- Trapezius muscle: detached

The distal clavicle appears to be displaced superiorly as the scapula and shoulder complex drop inferomedialy.

Clavicle elevated above the superior border of the acromion but coracoclavicular distance is less than twice normal (i.e. <25mm)

Type IV

All structures are disrupted like stage 3, and distal end of the clavicle is displaced posteriorly into or through trapezius muscle while the force applied to the acromion drives the scapula anteriorly and inferiorly.

This is a very rare injury.

Structures involved

- Acromioclavicular ligament: ruptured

- coracoclavicular ligament: ruptured

- Joint capsule: ruptured

- Deltoid muscle: detached

- Trapezius muscle: detached

Type V

All the structures are damaged as in stage II or IV.

Clavicle and acromion are widely separated.

All the soft tissues attaching the distal clavicle has been stripped and the bonw lies subcutaneously near the base of the neck.CC

Clavicle is markedly elevated and coracoclavicular distance is more than double normal (i.e. >25 mm)

Type VI

Ligaments and other structures are disrupted, and distal clavicle is dislocated inferior to coracoid process and posterior to biceps and coracobrachialis tendons.

The clavicle is inferiorly displaced behind coracobrachialis and biceps tendons. It is rare.

Clinical Presentation

The patient comes with pain in the superior part of the shoulder after a fall on the apex of the shoulder or outstretched hand.

The shoulder is swollen and generalized tenderness of the shoulder is noted.

The prominence of the distal clavicle may be noted.

The acromioclavicular joint is particularly tender.

In types I and II sprains, the deformity is usually minimal.

In type III injuries, the distal clavicle is abnormally prominent.

The patient has a limited range of motion and attempting the motion is painful.

Simultaneous examination of the contralateral shoulder may help.

In a delayed presentation, the complaint may be of the pain with specific exercises/activities such as the bench press and dips.

In addition, there would be a pain in the night, especially when rolling onto the involved shoulder.

Popping or catching in the region of the acromioclavicular joint may be reported by some patients.

Cross Body Abduction Test

This test assesses the stability of the affected shoulder. The patient elevates the arm on the affected side 90°, while the examiner grasps the elbow and adducts the involved arm across the body.

Although reproduction of pain with this maneuver may occur in patients with posterior capsule tightness or subacromial impingement, pain is suggestive of acromioclavicular joint pathology. The test should not be done in acute conditions.

The shoulder should be examined in detail to rule out concomitant injuries.

A distal neurovascular examination must be carried out.

If there is a doubt, the findings may be clearer when the patient is asked to hold a 10- to 15-pound weight in the hand of the affected arm.

Differential Diagnoses

- Clavicle Fractures

- Rotator Cuff Injury

- Shoulder Dislocation

- Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

- Superior Labrum Lesions

Imaging

X-rays

Imaging helps to confirm the diagnosis and differentiate acromioclavicular injuries from other shoulder injuries, clavicle injuries or scapula injuries.

A minimum of two views (eg, anteroposterior, lateral, axillary views of the shoulder are done. Lateral views of the scapula are desirable.

A radiograph of the entire upper thorax showing bilateral acromioclavicular joint is useful to compare the vertical distance between the clavicle and the coracoid process on both sides.

Following may suggest injury to the acromioclavicular joint

- Soft tissue swelling/stranding

- maybe the only finding in grade I

- Widening of the AC joint

- normal: 5-8 mm (narrower in the elderly)

- > 2 mm asymmetry than the contralateral side)

- Increased coracoclavicular distance

- normal: 10-13 mm

- > 5 mm asymmetry than the contralateral side

- Superior displacement of the distal clavicle [normally undersurface of the acromion is at level with the under the surface of the clavicle]

The severity of injury on radiographs is assessed as below:

- Type I: Normal

- Type II – Subluxation of acromioclavicular joint space < 1 cm, normal coracoclavicular space

- Type III – Subluxation of the acromioclavicular joint space > 1 cm, widening of the coracoclavicular space > 50%

- Types IV-VI: Findings in type III and associated displacement of the clavicle

With complete acromioclavicular/coracoclavicular ligament rupture, cross-body adduction films will show the scapula rotated anteromedially, and the acromion will migrate medially.

Stress views

Additional stress views may be done when

- Normal initial x-rays but there is a strong suspicion of the injury.

- For making the decision for surgery in a grade III injury

- In a follow-up to assess the stability of joint

Stress views are taken after attaching 5-7 kg weights to the wrist of the affected side, and an AP view can be taken. This stress tests the integrity of the coracoclavicular ligament.

If the joint is normal, then acromioclavicular alignment should stay normal and symmetric.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging is not generally required in the routine management of these injuries.

It can be considered in following cases

- Differentiating between type II and type III injuries

- Check for a possible rotator cuff tear

- To know the injury to the cartilaginous disc.

Treatment of Acromioclavicular Injuries

Depending on severity, acromioclavicular injuries can be treated conservatively or operatively.

As a general rule, type I and II are managed with conservative treatment and type IV, V, VI require surgery.

Type III can be managed both surgically and conservatively.

The occupation of the patient affects the choice of treatment. Surgical treatment can be considered for persons who have a high level of activity of upper limbs such as soldiers, athletes or heavy laborers.

Following points should be taken into account while planning for the treatment-

- Open fractures, neurovascular injury, and those with compromised skin should be treated surgically.

- Injuries requiring open reduction and internal fixation should be repaired within 2 weeks of injury.

- Standard surgical treatment is a reconstruction of the torn coracoclavicular ligaments

- For type III-VI injuries open reduction and stabilization of the dislocation with the repair of deltotrapezial fascia has also been described.

- Fixation is done with K-wires or screws

- With late arthritic changes, clavicle excision is considered.

The presence of infection is a contraindication to repair.

Treatment of Different Stages of the Acromioclavicular injuries

Type I

- Intrinsically stable injuries

- Sling application, activity modification, ice, and analgesic agents.

Patients get better in 1-2 weeks. Patients who have pain beyond this period may require steroid injections.

Those patients who have prolonged pain may require excision of the distal clavicle.

Type II

Treatment is similar to type I injuries followed by rehabilitation.

Strap immobilization for 2-4 weeks and avoiding heavy activity for 6-12 weeks are appropriate.

Type II injuries take longer to improve than those with type I injuries.

Type III

The patients who require nonoperative treatment are managed like type II injuries.

If the trial of conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment must be considered. Persons with active occupations like baseball pitchers, manual laborers, and soldiers Surgery in these people offers greater benefits.

Reconstruction of the torn coracoclavicular ligaments with either local tissue or an allograft is the standard procedure.

Type IV-VI Injuries

Surgical repair is the norm.

Open reduction and internal fixation is required along with repair of the deltopectoral fascia. Coracoclavicular screw or a trans-acromioclavicular joint pin is used for stabilization.

Patients undergoing reconstructive procedures remain in a sling for 2 weeks followed by the range of motion exercises. Progressive functional use is allowed at 6 weeks. Any hardware is device is removed by 6 weeks postoperatively.

Physiotherapy is continued until the patient’s range of motion and strength are maximized. The heavy physical use of the shoulder is prohibited for an additional 6 weeks.

The patients who undergo distal clavicle resection are simply protected in a sling for 2 weeks to allow soft-tissue healing.

Prognosis and Complications of Acromioclavicular Injuries

- Grade I and II injuries

- Persistent pain and late radiographic changes

- More than half of the patients have good to excellent functions after 5 years.

- Severe injuries

- Impingement symptoms secondary to the drop down of the shoulder and the abnormal biomechanics.

- Muscle-fatigue

Other complications from acromioclavicular joint injuries include-

- Cosmetic deformity

- Accelerated degeneration of the joint

- Decreased shoulder range of motion/upper extremity strength

- Distal clavicle osteolysis

Pediatric Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

Acromioclavicular joint injuries in children are rare. The immature clavicle is encased in a periosteal tube. The coracoclavicular ligament is within this tissue, whereas the acromioclavicular ligament is exterior to it.

Therefore, the acromioclavicular ligament is frequently injured but the coracoclavicular ligament is not.

References

- Shaffer BS. Painful conditions of the acromioclavicular joint. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999 May-Jun. 7(3):176-88.

- Goss TP. Double disruptions of the superior shoulder suspensory complex. J Orthop Trauma. 1993. 7(2):99-106.

- Macdonald PB, Lapointe P. Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008 Oct. 39(4):535-45, viii.

- Allman FL Jr. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967 Jun. 49(4):774-84.

- Nemec U, Oberleitner G, Nemec SF, Gruber M, Weber M, Czerny C, et al. MRI versus radiography of acromioclavicular joint dislocation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Oct. 197(4):968-73

- Press J, Zuckerman JD, Gallagher M, Cuomo F. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular separations. Operative versus nonoperative management. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997. 56(2):77-83.

- Rolf O, Hann von Weyhern A, Ewers A, Boehm TD, Gohlke F. Acromioclavicular dislocation Rockwood III-V: results of early versus delayed surgical treatment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008 Oct. 128(10):1153-7.

- Phillips AM, Smart C, Groom AF. Acromioclavicular dislocation. Conservative or surgical therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998 Aug. 10-7..

- Lizaur A, Sanz-Reig J, Gonzalez-Parreño S. Long-term results of the surgical treatment of type III acromioclavicular dislocations: an update of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Aug. 93(8):1088-92.