Last Updated on November 22, 2023

Swimmer’s shoulder is an umbrella term covering a range of painful shoulder in the competitive swimmer lead to a spectrum of overuse injuries seen in the swimmer’s shoulder, the most common of which is rotator cuff tendinitis.

Shoulder pain is the most common musculoskeletal complaint in swimming with swimmer’s shoulder.

Reports of incidence of disabling shoulder pain in competitive swimmers ranging from 27% to 87%.

Relevant Anatomy of Shoulder

[Read anatomy of shoulder]

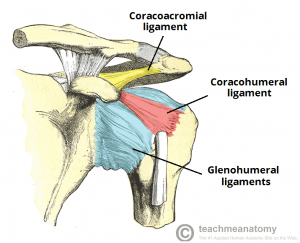

The shoulder girdle is anatomically designed to achieve the greatest range of motion. Glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints part of this system designed for the mobility whereas the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints provide stability along with tendon ligaments and muscles.

This mechanism allows the shoulder to withstand large external forces while providing enough mobility. It is especially true for overhead movements.

It is composed of

3 bones

- Scapula

- Clavicle

- Proximal humerus)

2 Joints

- Glenohumeral

- Acromioclavicular

Various ligaments, muscles, and tendons stabilize and enhance the function of the shoulder.

The subacromial bursa is present between rotator cuff and acromion provides the cuff with some mechanical protection.

There are three glenohumeral ligaments (inferior, middle, superior), which are thickened regions of the joint capsule. The inferior glenohumeral ligament is most important. Their role is to help stabilize the glenohumeral joint.

Rotator cuff is formed by the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor.

It functions as the dynamic and functional stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint with contributions from the long head of the biceps tendon

These ligaments, tendons, and muscles can be overused and injured in activities like swimming where the shoulder has a dominant role to play.

Out of these, the supraspinatus is most commonly injured.

The other muscles involved in activity are those which power the shoulder movements [ the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis, and deltoid] are less common to sustain an injury.

External stabilizers of shoulder girdle are the trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboids, and serratus anterior muscles. These also help n positioning the scapula and shoulder girdle and play important role in swimming.

These are also less commonly injured.

Biomechanics of Swimming

Swimming requires several different shoulder motions

- Circumduction in clockwise and counter-clockwise directions

- Varying degrees of internal and external rotation

- Scapular protraction and retraction

There are four different types of stroke in swimming – freestyle, butterfly, backstroke, and breaststroke. Most strokes are divided into two primary phases referred to as the pull-through and recovery. The pull-through is where propulsion is achieved.

Increased shoulder flexibility and range of motion are desirable and beneficial to all strokes. But this can lead to increased laxity of the glenohumeral joint capsule and ligaments and hence affecting stability.

The acquired anterior laxity permits excessive external rotation but places greater demand on the rotator cuff and the long head of the biceps to reduce humeral head elevation and anterior translation.

The rotator cuff tries to balance this laxity, to keep the humeral head centered in the glenoid socket during the stroke. It acts as a fulcrum of upper limb as it works through the water. It stabilizes the glenohumeral joint to allow efficient use of power by power muscles.

Failure of the rotator cuff and the scapular stabilizers to can lead to excessive humeral head migration and either increased tensile stress on the tendons or compression of the tendons due to the humeral head abutment.

It has been found that after about 3 months of training, subacromial space distance decreases in swimmers and there is an increase in forward shoulder posture compared to other athletes who do not have so much overhead shoulder use.

The proposed mechanism of failure initiates muscle fatigue. During high demands, rotator cuff muscles generally fatigue before the power muscles, allowing micromotion and subluxation of the humeral head.

This can lead to decreased stroke efficiency and may injure the rotator cuff, biceps tendon, and glenoid labrum.

Superior subluxation of the humeral head impinges the rotator cuff tendons against the acromion above, leading to tendinitis and/or tears.

Bursitis can result in the overlying subacromial bursa.

Primary subacromial impingement and secondary impingement may be contributive.

Another proposed impingement mechanism involves the microvasculature of the rotator cuff.

With shoulder abduction, vessels of the supraspinatus and long head of the biceps are filled and emptied during adduction causing vascular compromise leading to fatigue.

In addition, overuse of the shoulder would cause microtrauma.

Clinical Presentation of Swimmer’s Shoulder

There is pain which at first occurs during or after swimming. Often it is ignored and it starts paining with non-swimming activities of the shoulder as well.

Eventually, the worsening may cause pain at rest too.

A history of a recent growth spurt, an increase in the level of training and competition, or both may be there.

A break from swimming may improve the condition but often recurs with swimming if no rotator cuff strengthening is done.

The pain is often poorly localized and felt deep in the shoulder, often in the posterior aspect of the shoulder or less commonly, at the deltoid insertion area of the upper arm.

On examination, a common postural deviation is often observed in swimmers called forward head, rounded shoulder posture.

This posture includes

- Increased thoracic kyphosis

- Decreased cervical lordosis

- Protracted scapulae

- internally rotated/anterior humeral head.

[This posture is seen in players without Swimmer’s shoulder also]

Soft tissue findings associated with this posture are

- Restricted anterior shoulder musculature

- Lengthened and weak medial scapular stabilizers,

- Tight glenohumeral posterior capsule

- Weak anterior cervical flexors

Physical examination of swimmer’s shoulder may reveal asymmetry, particularly in scapular position, or rotator cuff muscle mass (atrophy).

Mostly, both internal rotation and external rotation are increased as compared to the general population.

Swimmers with impingement may have a painful arc from 60-120 degrees.

Weakness in the involved muscle, most commonly the supraspinatus, may be noted in advanced cases.

Altered scapulohumeral rhythm may be observed with excessive elevation or upward rotation of the scapula.

The range of motion will usually show excessive external rotation and horizontal abduction due to hypermobility of the anterior glenohumeral joint capsule.

In most swimmers’ shoulders, a mild-to-moderate increase in laxity is noted, indicating multidirectional laxity. Occasionally, this can lead to symptomatic instability in which the swimmer complains of the shoulder subluxing or shifting with use.

Following signs may be noted

- Sulcus sign [hypermobility]

- Positive load and shift test

- Positive relocation test

- Positive apprehension sign.

The weakness of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers will be noted when instability is present.

Positive impingement tests and painful resisted tests indicate underlying inflammation.

Shoulder Apprehension Test

Place the shoulder in maximum abduction and external rotation (90-90 position) and apply an anteriorly-directed force to the shoulder from behind. To be positive, it must elicit a feeling of apprehension or instability. Generally, the only discomfort is seen in swimmers rather apprehension or sense of instability.

Load and Shift Test

With the patient seated, stabilize the scapula to the thorax with one hand, while the other hand is placed across the posterior glenohumeral joint line and humeral head, and the web space across the patient’s acromion. The index finger should the over the anterior GH joint line.

Load and shift of the humeral head across the stabilized scapula in an anteromedial direction to assess anterior stability, and in a posterolateral direction to assess posterior instability is done.

Normal motion anteriorly is half of the distance of the humeral head, more movement is considered to be a sign of glenohumeral joint laxity.

Strength Assessment of Rotator Cuff

Subscapularis

- Internal rotation movement against resistance

- Lift-off test

- Shoulder in internal rotation with the back of the patient’s hand against the small of the back.

- The patient attempts to lift hand away from back against the examiner’s resistance.

Infraspinatus, teres minor

External Rotation against resistance [shoulder in the neutral position at the side and the elbow flexed to 90°.

Supraspinatus

- Resisted shoulder elevation with the arms extended, internally rotated, and positioned in the scapular plane (approximately 30-45° anterior to the coronal plane).

- If weak, retest the supraspinatus in the same arm position except with the arms externally rotated (ie, thumbs pointing upwards).

Sulcus Sign [Assessment of Joint Laxity]

The arm is pulled inferiorly and gap or sulcus is looked between the humeral head and lateral edge of the acromion. This indicates inferior subluxation of the humeral head.

- Grade 1 – Less than 1 finger breadth (< 1 cm)

- Grade 2 – One finger breadth (1-2 cm)

- Grade 3 – Greater than 1 finger breadth (> 2 cm)

Compare to the opposite shoulder (should be similar). If not then consider unilateral traumatic injury.

In addition, check for generalized ligamentous laxity.

Tests for Labral Tear

A labral tear is suggested by a painful click is noted during the recovery phase of an overhand stroke. Often, this click can be reproduced during the exam.

O’Brien test for Labral Tear [SLAP Lesion]

A downward force is applied with the extended in the forward flexed position, adducted 15° toward the midline, with the shoulder in the maximal internal rotation (thumb pointing down).

A pain that occurs in this position and relieved when external rotation is done suggests a SLAP lesion.

Differential Diagnoses

- Acromioclavicular Joint Injury

- Labral Tears

- Biceps Tendinopathy

- Bony Avulsion of Anterior Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament

- Cervical Radiculopathy

- Rotator Cuff Tear

- Multidirectional Instability

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

- Subacromial Bursitis

- Supraspinatus Tendonitis

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Lab Studies

Generally normal.

Imaging Studies

X-rays

X-rays are performed to rule out bony causes of shoulder pain like a stress fracture or lesion or loose body. X-rays should be obtained if the pain persists after 6 weeks of rest and rehabilitation.

The desirable x-rays are anteroposterior (AP) y-scapular or outlet view and axillary view of the shoulder.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is able to tell about rotator cuff pathology and status of the bones, ligaments, and other tendons in the shoulder.

But in most of the cases, the MRI is normal or in some cases may demonstrate some increased signal in the substance of the supraspinatus tendon.

Fluid in the subacromial bursa may signify bursitis.

MRI arthrogram with intraarticular gadolinium is able to depict labral tear.

Diagnostic Subacromial Injection

Subacromial injection of an anesthetics agent like lignocaine can be used for diagnosis. Immediate relief of pain following the injection suggests an injury of the rotator cuff and/or the overlying bursa.

Intra-articular injection providing relief, on the other hand, suggests intraarticular pathology.

Treatment of Swimmer’s Shoulder

In the acute phase, pain relief is the main aim. This involves

- Resting the shoulder.

- Modify/restrict activities

- Regular icing

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications or NSAIDs

For the restoration of strength, physical therapy and exercise follow. Measures taken could involve

- Supervised exercise program for the rotator cuff

- Ultrasound

- Phonophoresis

- Iontophoresis

- Electrical stimulation

Surgery for Swimmer’s Shoulder

If the patient does not improve even after 6 months of guided rest and rehabilitation.

The procedures include a diagnostic arthroscopy and a surgical tightening of the lax capsule (capsulorrhaphy).

If there is an evidence of impingement on arthroscopy, a subacromial decompression is performed.

After decompression surgery patient may not return to the same level of swimming. The athlete should know this before undergoing the procedure

After capsulorrhaphy, immobilization in an arm sling or immobilizer for 4-6 weeks is done.

After this rotator cuff strengthening program in physical therapy.

Before swimming, 80% of normal motion and strength in the shoulder should be there.

The patient with Swimmer’s shoulder can return to swimming between 6 and 12 months following surgery.