Last Updated on August 8, 2019

Atlantoaxial instability implies excessive movement between the first cervical vertebra or atlas, and second cervical vertebra or axis.

Atlantoaxial joint is formed between these two vertebrae This joint is a kind of transition zone and the instability may occur because of bony or ligamentous instability.

The instability can be asymptomatic or cause neck pain and neural symptoms when spinal cord or nerve roots are involved.

Trauma, and degenerative changes in rheumatoid arthritis, and to some extent infection are major causes of this instability in adults.

Multiple congenital and genetic causes [see below] including Down syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta are also associated with increased risk.

There is no preponderance for any age group and there is no racial predilection.

Pathophysiology

[See anatomy of cervical spine]

The integrity of the atlantoaxial joint is maintained by transverse apical alar ligament complex formed by

- The transverse ligament is the most important stabilizer

- Apical ligament

- Paired alar ligaments [parasagittal]

The transverse ligament acts as the primary restraint against anterior translation of the C1 on C2. The odontoid is the primary restraint against posterior translation.

The following three patterns of atlantoaxial instability are noted

- Flexion-extension

- Distraction

- Rotation

The instability is caused by bony or soft tissue changes in odontoid or tansverse ligament.

Odontoid changes could be due to

- Abnormal development of ossification

- Ossification of the odontoid

- Fracture of C1 or C2

- Destruction by tumor

The transverse ligament may undergo changes because of

- Ligamentous laxity due to abnormal protein [Down syndrome]

- Inflammation of the ligament [rheumatoid arthritis]

An abnormality or trauma can also be responsible for instability in C1-C2 joint.

Neural symptoms result when

- Subluxation or dislocation causes cord compression

- by the odontoid process or

- posterior arch of the atlas.

- Motion of the C1-2 segment can cause compression of nerve roots.

Vertical displacement of the atlas requires widening of the C1-2 facet joint which may be caused by breakage of the alar ligament, cruciate ligament, the tectorial membrane, or a combination.

Rheumatoid inflammation can destroy cartilage causing weakness of the transverse and alar ligaments and facet capsule. Movement at C1-C2 attenuates them further contributing to the instability.

Grisel syndrome refers to the atlantoaxial subluxation following inflammation of adjacent soft tissues after a pharyngeal infection or surgical intervention. It is primarily seen in children aged 5-12 years. A steeper dens-facet angle and rich vascularity in children makes them more susceptible.

In individuals with Down syndrome, the primary cause of AAI is the laxity of the transverse ligament.

It is rare to see atlantoaxial instability without a predisposing factor. Different conditions have different risks associated. Some known examples are

- Down syndrome – 13-15%

- Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia – 40%

- Morquio syndrome – Almost 100%

- Chondrodysplasia punctata – About40-50%

- Metatropic dysplasia – 75%

Causes of Atlantoaxial Instability

The following conditions can be associated with AAI:

- Down syndrome

- Congenital scoliosis

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Neurofibromatosis

- Morquio syndrome

- Larsen syndrome

- Dysplasia/Aplasia/Hypoplasia

- Spondyloepiphysea congenita

- Chondrodysplasia punctata

- Metatropic dysplasia

- Kniest syndrome

- Achondroplasia

- Pseudoachondroplasia

- Cartilage-hair hyperplasia

- Abnormalities upper cervical spine

- Os odontoideum

- Ossiculum terminale

- Hypoplasia or absence of the dens

- Third condyle

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Infections

- Tumors

- Trauma

-

- Type I odontoid fracture (very rare)

- Atlas fractures

- Transverse ligament injuries

- Cerebral palsy

- Steroid treatment

- Idiopathic laxity of the transverse ligament.

The causes vary with age group.

Common nontraumatic causes in adults are Down’s syndrome, rheumatoid Arthritis, os odontoideum whereas juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and Morquio syndrome are common in children.

Trauma or infection in children can lead to rotatory atlantoaxial subluxation.

Spinal cord compression can arise or worsen if susceptible spines are subjected to extreme ranges of motion. The complications include.

- Spasticity

- Myelopathy

- Neck pain

- Radicular symptoms

Classification [Fielding and Hawkins]

Type I

Simple rotatory displacement with an intact transverse ligament

Type II

- Anterior displacement of C1 on C2 of 3-5 mm

- One lateral mass serving as a pivot point

- Deficiency of the transverse ligament

Type III

Anterior displacement exceeding 5 mm

Type I

Posterior displacement of C1 on C2

Both type III and type IV are highly unstable.

Clinical Presentation

The patient could be asymptomatic in many cases.

Neck pain, heaviness and neural symptoms are the usual presenting symptoms.

Patients with congenital anomalies are usually without symptoms till the third decade of life as the spine is able to accommodate. With age, degenerative changes and rigidity causes increasing loads on atlantoaxial joint.

In individuals with rotatory displacement, torticollis can be the presenting symptom.

Symptomatic patients in rheumatoid arthritis with atlantoaxial instability can present with occipital pain.

Some patient may have myelopathy, vertigo, brainstem signs, or lower cranial nerve palsies.

The cases with trauma and post-infection atlantoaxial instability [Grisel syndrome] would have a preceding history. Tenderness over the spinous process of the axis and displacement of spine of the axis in the direction of head tilt [head tilt] may be noted in cases of instability after infection.

In the case of congenital deformities or syndromes, the neck examination is warranted to look for asymptomatic cases. This is especially true in Down syndrome, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Morquio syndrome, chondrodysplasia punctata, and metatropic dysplasia.

Physical examination should include a detailed neurologic examination including. Upper motor neuron signs could indicate symptomatic atlantoaxial instability.

Commonly seen signs are increased reflexes, weakness of the muscles, broad-based gait, decreased hand dexterity, loss of motor milestones and bladder problems.

Somatosensory evoked response may reveal information regarding neurologic involvement.

Persons with AAS due to inflammatory processes less frequently exhibit signs of root or cord involvement.

Lab Studies

No laboratory studies are relevant.

Children presenting with atlantoaxial instability should be screened for genetic conditions which may be associated.

Imaging

X-rays

Standard views include open-mouth odontoid and lateral cervical spine radiograph. For better accuracy, the lateral view can be done in flexion, extension and flexion position.

The measurements for the cervical spine are done.

Lateral mass spread

Lateral mass are connected by a ring of C1 and can only be displaced if there is a disruption of the ring or the transverse ligament is ruptured

Measurement is done on the open-mouth view

- The combined spread of lateral masses of C1-C2 should not be more than 6.9 mm

- If more, it indicates transverse ligament rupture

- If greater than 8.1 mm injury is unstable

Atlantoaxial distance

- On lateral x-ray

- Indicates instability if more 4-5 mm

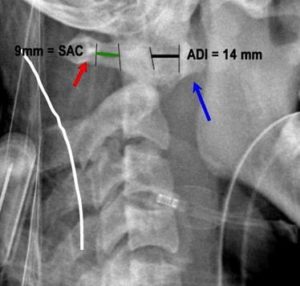

Atlantodental Interval or Atlanto-dens interval (ADI)

It is the distance between the odontoid process and the posterior border of the anterior arch of the atlas. In children, the value is less than 4 mm in lateral view with a neck in a neutral position. Measurement should be made in both flexion and extension views.

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a value of more than 10mm indicates the need for surgery.

Posterior Atlanto-dens-interval [PADI] or Space-available-cord [SAC]

It is measured as the distance from the surface of dens to the anterior surface of the posterior arch of atlas.

In adults, less than 14 mm is associated with increased risk of neurologic injury and is an indication for surgery.

CT/MRI

CT is able to provide more information on stability.

Rotatory displacement are difficult to measure on plain x-rays and are better depicted by CT especially with image reformatting.

MRI provides better imaging of soft tissues and neural tissues.

Treatment of Atlantoaxial Instability

Unless symptoms of spinal cord compression occur, AAI requires no treatment.

Once symptoms arise, cervical spine stabilization is indicated until surgical stabilization is performed.

There are no pharmacologic interventions for atlantoaxial instability.

In persons with rotatory displacement, the time of presentation dictates the treatment. Most of these patients’ conditions resolve spontaneously, and additional care is not sought.

Acute subluxations [less than one week] are treated with a soft collar and rest for a week. If the reduction does not occur, halter traction with analgesics and muscle relaxants is warranted.

If still the reduction does not occur, halo brace is applied.

A rotatory displacement more than 1 month’s duration is put on halo traction for 3 weeks is tried. Surgery is indicated if the reduction does not occur and there is a fixed deformity.

Fielding and Hawkins classification can be used as a rough guide-

- Type I – Stable, treated in a collar

- Type II – Potentially unstable, individualize the treatment conservative or surgical

- Type III, IV- Unstable, requires surgical stabilization

- Atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS) of greater than 8 mm with evidence of cord compression on dynamic flexion-extension view

- Posterior atlantodental (or atlanto-dens or atlas-dens) interval (ADI) of 14 mm or less

- More than 3.5 mm of subaxial subluxation

- Progressive neurologic deficit

The aim of the surgery is

- Protection of the spinal cord

- Stabilization of spine

- Decompression of neural tissue

- Correction of deformity

- Reduction of deformity

Pure ligamentous injuries usually do not heal themselves and require C1-C2 fusion.

In case a bony avulsion is seen with ligamentous injury trial of conservating treatment by halo brace can be given.

Options for fixation implant include

- Transarticular screws posteriorly

- Screw-rod constructs along the C1 lateral mass and C2 pedicle

- Posterior sublaminar wiring

- Halifax clamp

Treatment decisions are also determined by specific conditions.

References

- Babic-Naglic D, Potocki K, Curkovic B. Clinical and radiological features of atlantoaxial joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 1999 Aug. 58(4):196-200.

- Evaniew N, Yarascavitch B, Madden K, Ghert M, Drew B, Bhandari M, et al. Atlantoaxial instability in acute odontoid fractures is associated with nonunion and mortality. Spine J. 2015 May 1. 15 (5):910-7.

- Wasserman BR, Moskovich R, Razi AE. Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine–clinical considerations. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011. 69(2):136-48.

- Yamazaki M, Someya Y, Aramomi M, Masaki Y, Okawa A, Koda M. Infection-related atlantoaxial subluxation (Grisel syndrome) in an adult with Down syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Mar 1. 33 (5):E156-60.

- Ahmed R, Traynelis VC, Menezes AH. Fusions at the craniovertebral junction. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008 Oct. 24 (10):1209-24.